A living entity is different from a dead entity because it self-maintains this difference. To live entails self-maintaining and self-constructing a “far from equilibrium state”. The work of Prigogine (1973) showed that, for thermodynamic reasons, such an inherently unstable system can only be maintained via a continual throughput of matter and energy (e.g., food and oxygen). Death coincides with the moment self-maintenance stops. From this moment on, the formerly living entity moves towards equilibrium and becomes an integral and eventually indistinguishable part of the environment.

A living entity “is” — exists — because it “does”: it satisfies its needs by maintaining the throughput of matter and energy by “adaptively regulating its coupling with its environment so that it sustains itself” (Andringa et al., 2015; Barandiaran, Di Paolo, & Rohde, 2009 p. 8). An autonomous organization that does this is called a “living agent” or an agent for short (Barandiaran et al., 2009). Note that we refer to an agent when the text pertains to life in general and is part of core cognition. Where we specifically refer to humans we use the term “person”. The term “individual” can refer to both, depending on context.

Life is precarious (Di Paolo, 2009), in the sense that it must be maintained actively in a world that is often not conducive to self-maintenance and where both action and inaction can have high viability consequences (including death). We refer to behavior as agent-initiated context-appropriate activities with expected future utility that counteract this precariousness and minimize the probability of death. Behavior is always aimed at remaining as viable as possible, since harm — viability reduction — can more easily end a low-viability than a high-viability existence.

A pattern of behaviors that effectively optimizes viability leads to flourishing, while a pattern of ineffective or misguided behaviors leads first to languishing and eventually to death. Life is “being by doing” the right things (Froese & Ziemke 2009, p. 473). Viability is a holistic measure of the success or failure of “doing the right things”, since it is defined as the probabilistic distance from death: the higher the agent’s viability, the lower the probability of the discontinuation of life. A walrus that falls off a cliff may be perfectly healthy, but it has zero viability, since it will die the moment it hits the ground. While healthy, it is in mortal and inescapable danger, and hence unviable. In general, threat signifies a perceived reduction of contextappropriate behavioral options that allow the agent to survive. Maximizing viability (flourishing) and minimizing danger (survival) constitute basic motivations of life. In fact, we call any system cognitive when its behavior is governed by the norms of the system’s own continued existence and flourishing (Di Paolo & Thompson, 2014). This is also a reformulation of “being by doing”.

Agency entails cognition: behavior selection for survival (avoiding death) and thriving (Barandiaran et al., 2009) (optimizing viability of self and habitat). We have argued that cognition for survival is quite different from cognition for thriving (Andringa et al., 2015). Cognition for survival is aimed at solving problems, where a problem is any perceived threat to agent viability, interpreted as a pressing need that activates reactive behavior. We called this form of cognition coping. In humans, (fluid) intelligence is a measure of problem-solving and task-completion capacity and manifests coping. The objective of coping is ending/solving the problems that activated the coping mode, so ideally coping is a temporary state. We refer to the problem-solving ability, including successful test and task completion ability (Gottfredson, 1997; van der Maas, Kan, & Borsboom, 2014), as intelligence.

However, when the agent’s problem solving is inadequate and problems are not solved and are potentially worsened or increased, the perceived viability threat remains activated and the agent is trapped in the coping mode of behavior. A coping trap keeps the agent in continued threatened viability, and hence in behaviors aimed at short-term self-protection in suboptimal states that are far from flourishing. Maslow (1968) calls this deficiency (D) cognition, since it is ultimately activated by unfulfilled needs. It is a sign that the intelligence of the agent failed to end (solve) problem states.

While the coping mode of behavior is for survival, the co-creation mode is for flourishing. Successful coping leads to solved problems and satisfied needs, and hence to its deactivation. Therefore, co-creation is the default mode of cognition and coping is — ideally — only a temporary fallback to deal with a problematic situation. Continued activation is the success measure of the co-creation mode and avoiding problems (or dealing with them before they become pressing) is, therefore, the main objective of co-creation. It is essentially proactive behavior (thus not just “proactive coping”, since successful coping leads to its deactivation). Maslow (1968) refers to co-creation as being (B) cognition, and we described it as pervasive optimization and “generalized wisdom”, for reasons which will become apparent. The objective of co-creation is pro-actively producing indirect viability benefits through self-guided habitat contributions that improve the conditions for future agentic existence.

This is known as stigmergy: building on the constructive traces of past behaviors left in the environment (Doyle & Marsh, 2013; Gloag et al., 2013; Heylighen, 2016b; 2016a) and that, in the aggregate, gradually increase habitat viability. This expresses authority as a shaping force in the habitat (Marsh & Onof, 2008), via influencing others through habitat contributions. Habitat is defined as the environment from which agents can derive all they need to survive (and thrive) and to which they contribute to ensure long-term viability of the self and others.

Habitat viability is a measure of the potential of the habitat to satisfy the conditions for agentic existence (i.e., satisfied agentic needs). For example, a habitat can be deficient in the sense that its inhabitants continually have unfulfilled needs (and hence are in the coping mode). The habitat can also be rich, so that pressing needs can easily be satisfied and co-creative contributions can perpetuate and enhance habitat viability.

The biosphere grew from fragile and localized to robust and extensive, so we know beyond doubt that life on Earth is, in the aggregate, a constructive force. It is the co-creation mode’s contributions to habitat viability that explain this. In fact, the biosphere can be seen as the outcome of stigmergy: the sum total of all agentic traces left in the environment since the origin of life (Andringa et al., 2015). Co-creation and generalized wisdom as the main cognitive ability drive the biosphere’s growth and gradually increase its carrying capacity: the sum total of all life activity in the biosphere. This makes co-creation the most authoritative influence on Earth. Coping is also an important authoritative influence, but it is limited to setting up and maintaining the conditions for pressing need satisfaction.

Figure 1 presents the co-dependence of acting agents on their habitat. The habitat comprises the aggregate of agentic activities, but is not an actor itself. Hence, a viable habitat is composed of the sumtotal of previous co-creative agentic traces that form a resource to satisfy the conditions on which current agentic existence depends. This entails that, signified by the question marks, agents should be aware not only of their own viability, but also of habitat viability. In fact, we have argued (Andringa, van den Bosch, & Weijermans, 2015) that early, primitive life forms were yet unable to separate self from the co-dependence of self and habitat. This leads to an “original perspective” on the combined viability of agent and habitat, which allowed their primitive cognition to optimize the whole, while addressing selfish needs and creating ever better conditions for agentic life. This can be termed pervasive optimization and it expresses an emergent purpose of life on Earth to produce more life. Albert Schweitzer (1998) formulated a slightly weaker version of this “I am life that wills to live in the midst of life that wills to live.”

Pervasive optimization is the driver of well-being. We propose that successful well-being, with a focus on ‘being’ and hence interpreted as a verb, can best be understood as a co-creation process leading to high viability agents, increased habitat viability, and long-term protection and extension of the conditions on which existence depends.

The two modes of behavior have quite different impacts on the habitat and, by extension, the biosphere. The coping mode is aimed at protecting and improving agent viability with whatever means the agent has access to. Since the objective is avoiding death, the motivation is high, which entails that habitat resources can be sacrificed for self-preservation purposes. Inadequacy can be defined as the tendency to self-create, prolong, or worsen problems that keep an agent in the coping mode. When a habitat is dominated by inadequate agents, as is characteristic of a social level coping trap, habitat viability cannot be maintained, let alone increased. From the perspective of coping, life is at best a zero-sum game.

Alternatively, adequacy can be defined as the ability to avoid problems or end them quickly so that coping is effective and rare. Now co-creation is prevalent so that habitat viability is protected, carrying capacity increases, and long-term need satisfaction is secured. Co-creation is, like the term suggests, a more than zero sum game. This is, as argued above, the true basis of well-being. Due to its lack of “co-creation”, coping protects lower levels of well-being and, at best, resolves (or otherwise takes care of) viability threats (in the sense of removing symptoms of low well-being), while co-creation allows both agent and habitat flourishing.

The inadequacy-adequacy dimension might underlie the proposed single dimension of psychopathology termed p (Lahey et al., 2012; Caspi and Moffit, 2018). This has been conceptualized as “a continuum between adaptive and maladaptive functioning”, “successful versus unsuccessful functioning”, a disposition for negative emotionality or impulsive responsivity to emotion, and unrealistic thoughts that manifest in extreme cases as delusions and hallucinations (Smith et al., 2020). All descriptions fit with our interpretation of inadequacy as the tendency to self-create, prolong, or worsen problems and adequacy as the ability to avoid problems or end them quickly.

Welzel and Inglehart (2010) argue, from the perspective of cultural evolution, “that feelings of agency are linked to human well-being through a sequence of adaptive mechanisms that promote human development, once existential conditions become permissive”, which is a formulation of the dynamics of Figure 1. They argue that “greater agency involves higher adaptability because for individuals as well as societies, agency means the power to act purposely to their advantage”. This uses the concept of agency as a measure of the ability to self-maintain viability, which is related to adequacy.

Living agents, per definition, need to express behavior to perpetuate their existence. And with every intentional action, the agent implicitly relies on the set of all that it takes as reliable (i.e., true in the sense of reflecting reality as it is) enough to base behavior on. We refer to this set as the agent’s worldview. A worldview should be a stable basis, as well as developing over time because it is informed by the individual’s learning history. An agent’s worldview informs its appraisal of the immediate environment. This may be an appraisal of its viability state: whether the habitat is safe or not, or whether it judges the current situation as manageable, too complex, or opportunity filled.

These are basic appraisals shared by all of life that seem to be reflected in the psychological concept of core affect (Russell, 2003). Core affect is a mood-level construct that combines the axis unpleasureable-pleasurable with an arousal axis spanning deactivated to maximally activated. It is intimately and bidirectionally linked to appraisal (Kuppens, Champagne, & Tuerlinckx, 2012; van den Bosch, Welch, & Andringa, 2018) and refers directly to whether one is free to act or forced to respond: whether one can co-create proactively or has to cope reactively. Hence appraisal is a worldview-based motivational response to the perceived viability consequences of the present state of the world. It is motivational, but not yet action. As such appraisal resembles Frijda’s (1986) emotion definition as ‘action readiness’. Which fits with the notion that all cognition is essentially anticipatory:

“Cognitive systems anticipate future events when selecting actions, they subsequently learn from what actually happens when they do act, and thereby they modify subsequent expectations and, in the process, they change how the world is perceived and what actions are possible. Cognitive systems do all of this autonomously.” (Vernon 2010, pp. 89).

The anticipation of the development of the world (comprising of self and environment) refers back to what we earlier introduced as the “original perspective” on the combined viability of agent and habitat, which allowed the first life forms to optimize the whole, while addressing selfish needs and creating ever better conditions for more agentic life. Core affect is a term adopted from psychology (Russell, 2003) that we here generalize to all of life. Core affect is a relation to the world as a whole and not a relation to something specific in that world. Like moods, core affect does not have (or need) the intentionality (directedness) of emotions and it is, unlike emotions, continually present to self-report (van den Bosch, Welch, & Andringa, 2018).

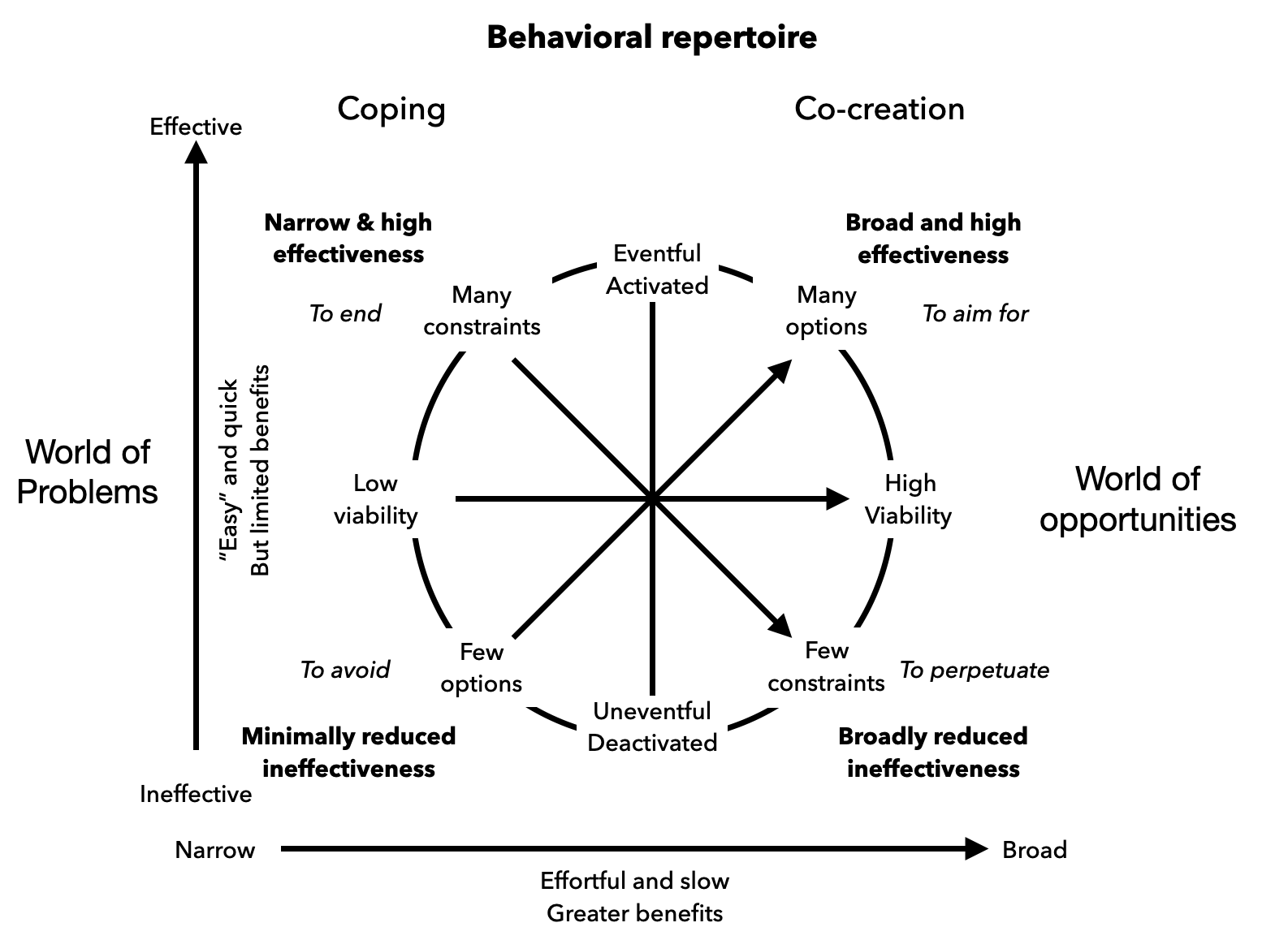

The human worldview is, of course, filled with explicit and shared beliefs, opinions, facts, or ideas interpreted with and filtered by experiential knowledge. This worldview informs whether the situation is deemed dangerous or not (whether avoidance or approach is appropriate). This holds also for a general agent: when the agent judges the situation as safe it can express unconstrained natural behaviors since it has to satisfy few constraints. If the situation is safe and opportunity-filled, it can be interested and learn. But if the situation imposes many constraints, it tries to end these by establishing control. And in a deficient environment the agent is devoid of opportunities (which in humans may correspond to boredom or, in case of lost opportunities, sadness). Core affect then is expressed as motivations to avoid or end (coping) or motivations to perpetuate or to aim for (co-creation). We have depicted this in Figure 2.

Appraisal of reality refers to the behavioral consequences of the current state of the world and it is a form of basic meaning-giving that activates a subset of context appropriate behavioral options (van den Bosch, Welch, & Andringa, 2018). This leads to motivation as being ready to respond to the context appropriately. We define the set of all possible – appraisal and worldview dependent – behaviors as the behavioral repertoire. The richer the behavioral repertoire, the more diverse context appropriate behaviors the agent can exhibit. The more effective its behavioral repertoire, the more effective it becomes in realizing intended outcomes and the more adequate the agent is. Conversely, the less effective the context-activated behaviors, the more inadequate the agent is. Learning either reduces the ineffectiveness of behaviors or it expands the behavioral repertoire.

Expanding the repertoire results from an individual discovery path through a representative sample of different environments and interactive learning opportunities. Broadening is effortful and potentially risky but ultimately rewarding. Fredrickson’s (2005) broaden and build theory fits here by proposing that positive emotions – indicating the absence of problems and hence co-creation – help to extend the scope of behavioral options. This type of learning leads to individual skills that are, through the individual discovery path, difficult to share. This manifests in humans as implicit or tacit knowledge (Patterson et al., 2010) and well-developed agency.

Reducing the ineffectiveness of behaviors is essential in problematic (coping) situations. This may entail adopting, through social mimicry, the behaviors of (seemingly) more successful, healthy, or otherwise attractive agents. The adoption of presumed effective behaviors manifests shared knowledge. Mimicry is a quick fix and works wherever and as long as the adopted behaviors are effective. As a dominant learning strategy, mimicry leads to a coordinated situation of sameness and oneness. The coordinated agents make their adequacy conditional to the narrow set of situations where the mimicked behaviors work. These agents may be intolerant to others who frustrate sameness and oneness. They may express this intolerance by selecting behaviors that enforce social mimicry on non-mimickers. The more they feel threatened, the more they feel an urge to restore the conditions for adequacy and the more intolerant to diversity they are. In humans this is expressed as the authoritarian dynamic (Stenner, 2005).

This discourse leads to a selection of core cognition key concepts with definitions.

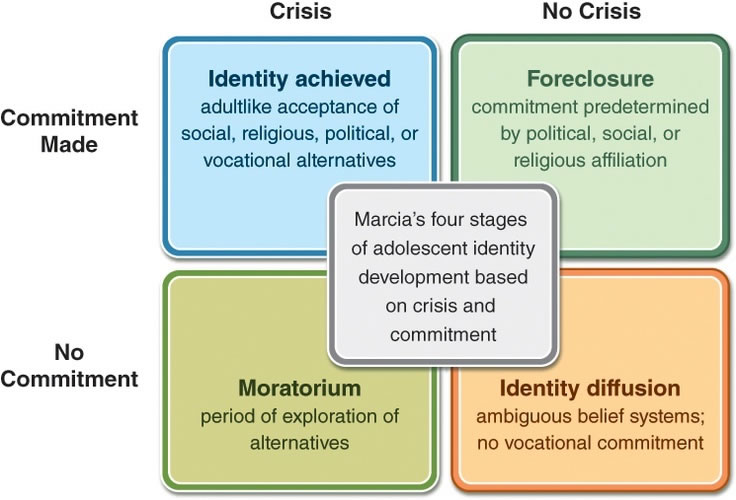

Here we develop the structure of identity in terms of coping and co-creation adequacy. This leads to an enriched understanding of the interplay between coping and co-creation, and it demonstrates that the conceptual language of core cognition is a productive lens for approaching a well-studied psychological phenomenon.

This section addresses two routes to social well-being. There are many routes to prospective well-being; in fact, all self-help literature and political, economic, or religious ideologies propose them. We have selected the “ontological security” framework and a recent formulation of “psychological safety” to represent very clear, actionable, and precisely-worded coping and co-creation alternative approaches to general well-being.

We derived two separate forms of cognition; coping: for addressing pressing problems and, hence, aimed at its termination; and co-creation: aimed at optimizing everything in the context of everything else and aimed at its perpetuation.