This is an accessible, but not simplified, text in which derive the features of mass formation and the associated mass cognition from basic features of life.

We show it predicts the properties of authoritarianism and canceling very well.

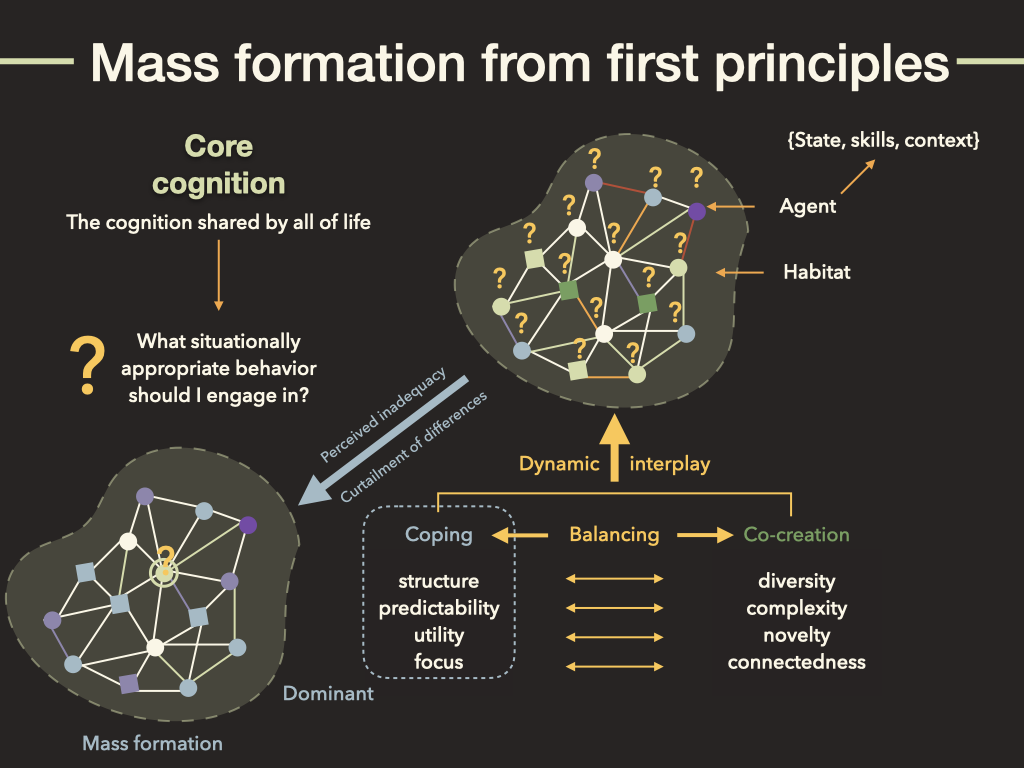

In this analysis we derive the features of mass formation and the associated mass cognition (authoritarianism) from the basic features of life. We do this from the theoretical perspective of core cognition: the hypothesized cognition shared by all of life.

Only a small part of this text concerns humans. Most of it pertains to all living agents. A key feature is of agents is agency: the ability to self-maintain existence.

Core cognition describes the basic requirements for the selection of situationally appropriate behavior. Selecting situationally appropriate behavior is what all living agents do, all the time.

Agents differ in state, skills, and context and they influence both each other and the habitat via their behaviors. Behavior selection is a continual process and is unique for each agent.

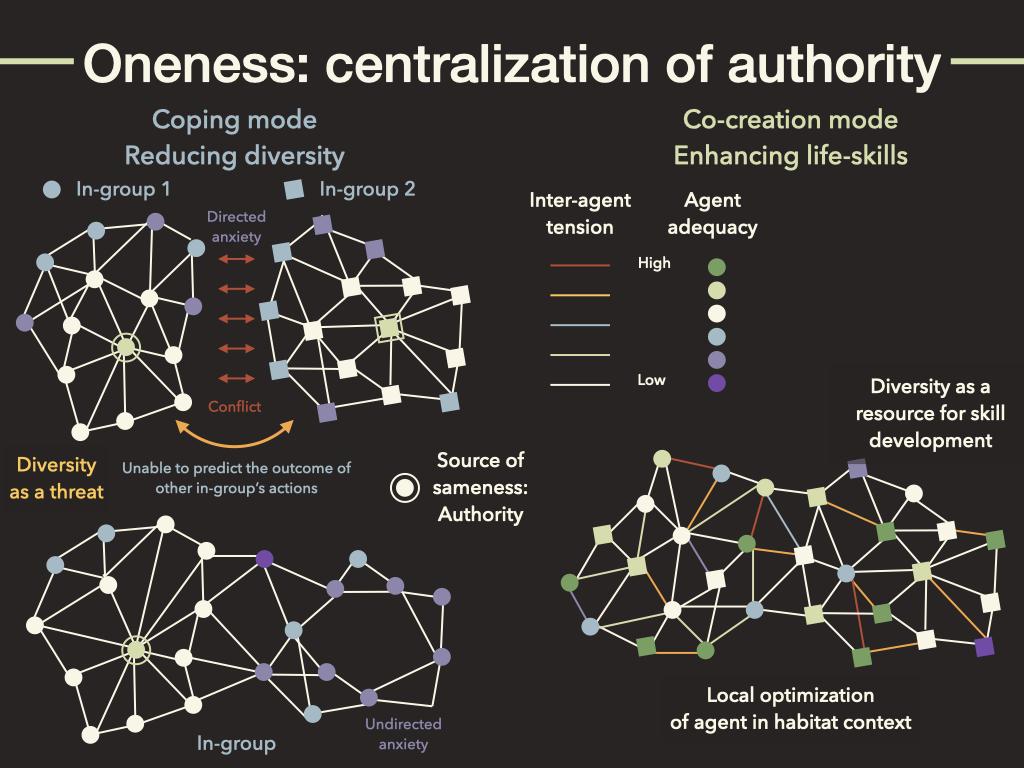

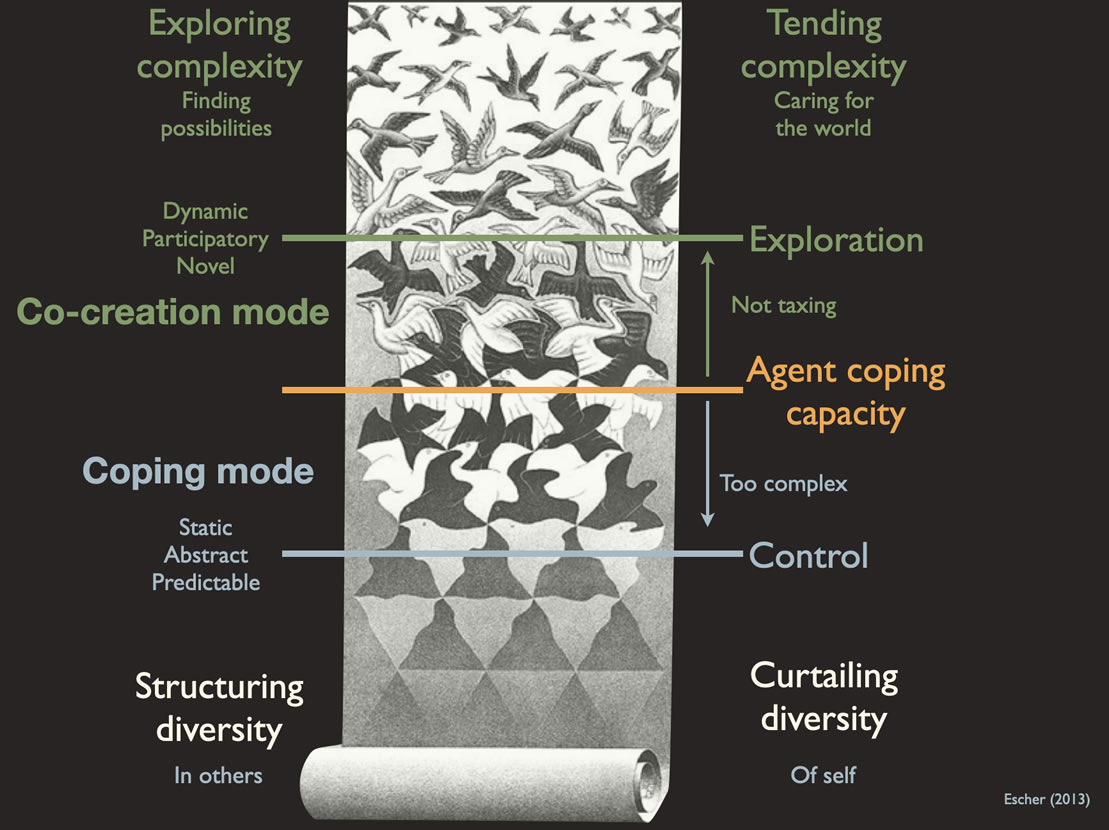

In this presentation we oppose two modes of being – coping an co-creation – as a caricature of the actual continual and mostly constructive, interplay between these modes.

However, mass formation emerges as a habitat wide dominance of coping through the suppression of co-creation in situations were agents are inadequate and respond by curtailing difference. In this extreme, it makes sense to temporarily dispense of nuance.

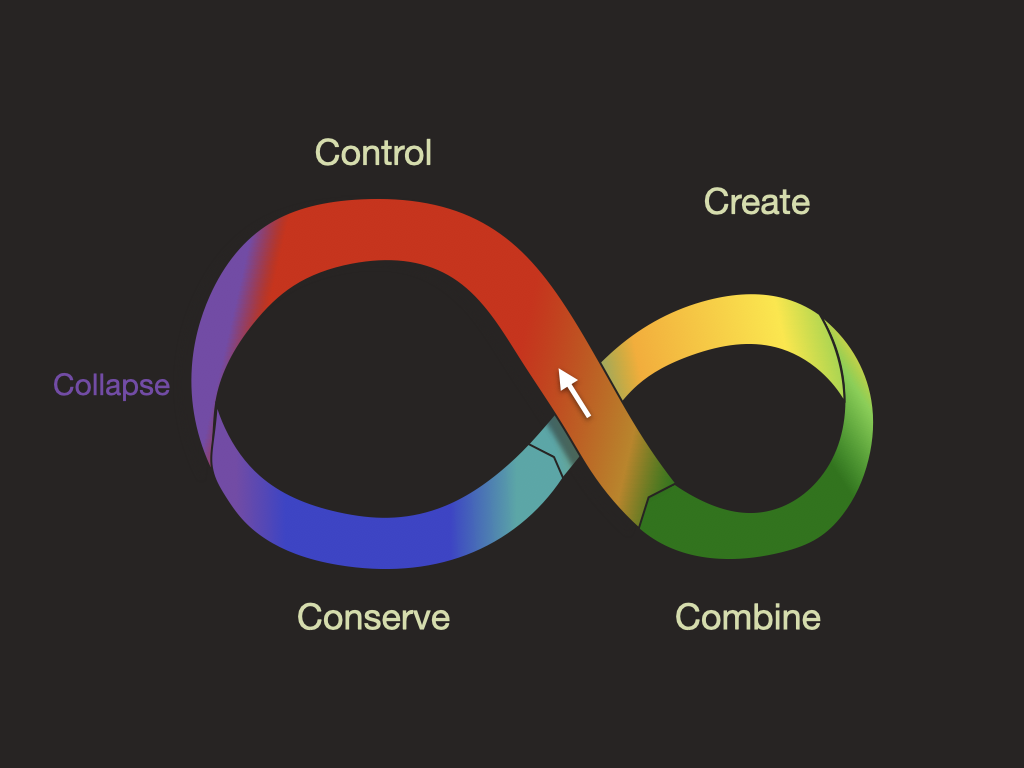

Coping and co-creation are balancing like yin and yang. Co-creation promotes diversity, complexity, novelty, and connectedness. Coping balances this by providing structure, predictability, utility, and focus. A productive interplay keeps the habitat vibrant and stable and allows its inhabitants to develop the skills to flourish.

This presentation focuses on what happens when habitat complexity exceeds the coping capacity of most inhabitants. The main text focusses on the introduction and description of phenomena. The footnotes provide literature references1 and illustrative comments2.

We start with some basics of core cognition.

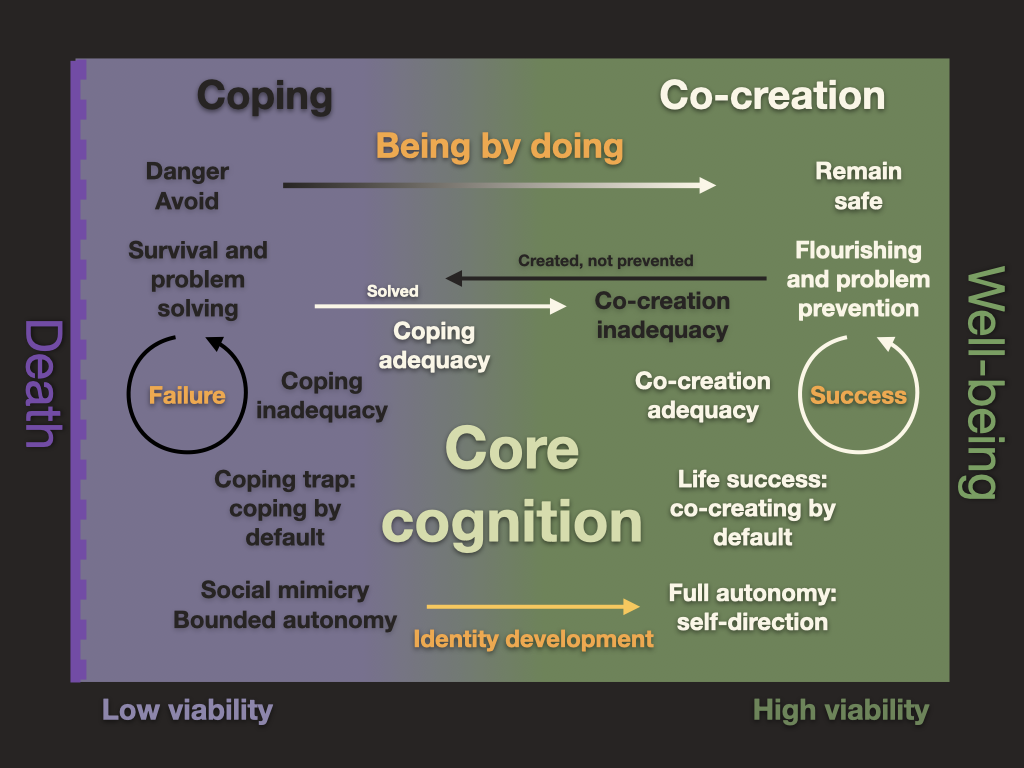

Life can be described as “being by doing”: (living) agents exists because they act in ways that allow them to avoid danger, low viability, and death. Individuals always aim to be and remain as safe and viable (far from death) as possible. They strive to be and remain well.

Cognition for survival and problem solving differs from cognition for flourishing and problem prevention. Cognition for survival and problem solving has particular start-states such as problem or threat and end-states: a threat that has been dealt with or a problem solved. Cognition for flourishing and problem prevention does not have particular start- or end-states and ideally continues indefinitely as a goalless progression of favorable states3.

We call cognition for survival and problem solving “coping” and cognition for flourishing and problem prevention “co-creation”. In case of life success, co-creation is the default and coping is only a temporary fallback intended to restore safety after co-creation failed.

We refer to co-creation adequacy if the agent succeeds in preventing most problems. It exhibits coping adequacy if it solves problems quickly and effectively.

Conversely co-creation inadequacy entails that agents are instrumental in creating their own problems states. And coping inadequacy if agents fail to end problems effectively.

In particular, if the coping mode of behavior leads to more or new problems or continued danger, it remains activated: a coping trap, where coping has become the default. Individuals in this state may never learn to become adequate co-creators. Life success requires that co-creation became the default mode of cognition.

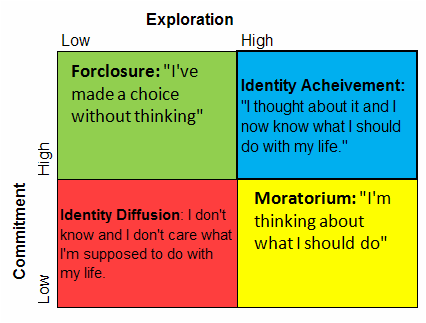

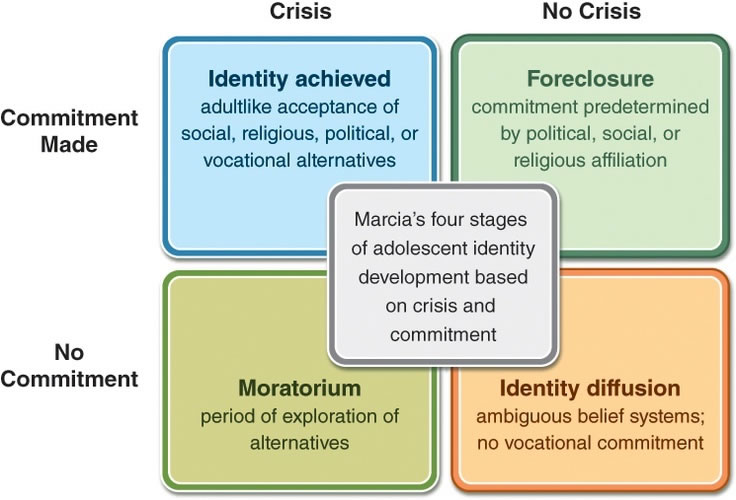

Living agents learn a lot from copying the behaviors of others. But to become fully autonomous self-directors they need to overcome the limits of social mimicry and following the lead of others. They must learn to trust their own decision-making; until that time they exhibit bounded autonomy. Development from bounded autonomy to full autonomy is central to successful identity development.

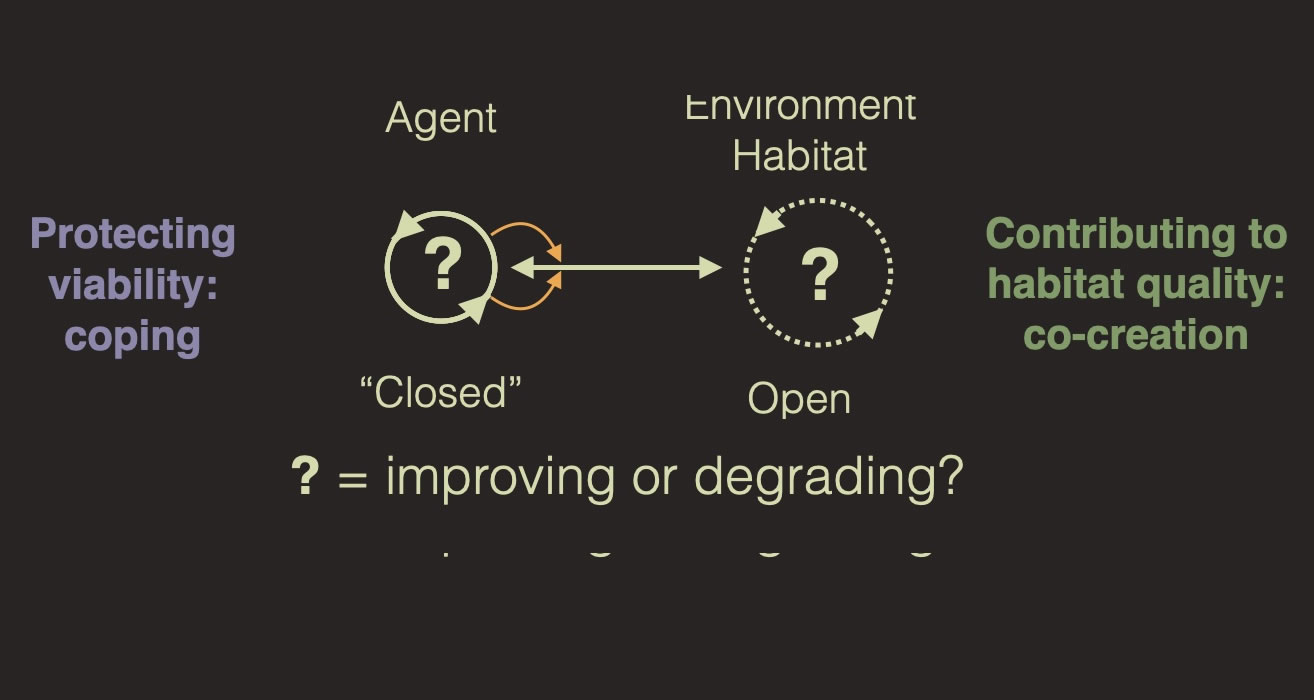

To remain alive agents must protect their viability by satisfying basic needs. But they must also contribute to the viability of their habitat, because all life depends on habitat resources to satisfy short and long term needs.

A surviving agent copes with pressing problems to protect its viability and generally takes more from its environment than it contributes. This is characteristic of coping.

A thriving agent contributes to a habitat in which pressing problems can mostly be avoided and habitat viability is maximized. This is a key feature of co-creation.

Dominant co-creation drove and drives the development of the biosphere. Conversely, dominant coping degrades the environment.

Living agency, or agency for short, is the ability to self-maintain existence. Agency manifests itself as bringing the co-dependance of self on the habitat in the service of self and the habitat. This naturally leads to a network of mutual dependency comprising all in the habitat.

In a self-stabilizing habitat, agents mostly express unforced self-initiated natural behavior that minimizes the occurrence of conflict and problems, and that stabilizes the habitat without ever aiming for particular stable states. Forests and human friendships express this dynamic.

Co-creation and coping successes are both the result of skilled behavior. Skilled co-creation entails furnishing the habitat with broadly constructive traces in a process called stigmergy.

Skilled coping entails the quick and effective resolution of problem states and it also provides the stable structure to benefit optimally from stigmergy.

In isolation, coping tends to utilize and exploit the (stigmergic) resources more than it builds them.

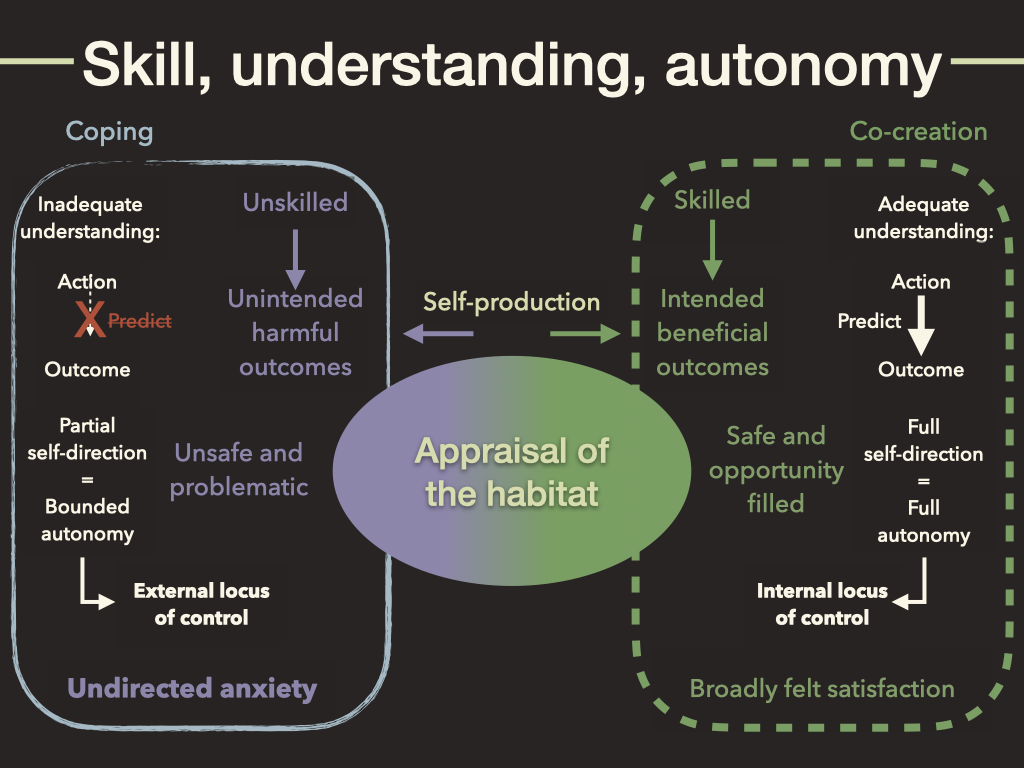

Behavior is skilled when the outcomes of an agent’s activities realize intended benefits. Unskilled behavior realizes unintended outcomes: the agent wastes energy or the behaviors cause harm to self or others.

Skilled agents can predict the pattern of outcomes of their agency and select course of actions with likely favorable outcomes This proves they adequately understand what they are doing.

Unskilled agents are ineffective and might produce unintended adverse outcomes: they insufficiently understand the link between action and outcome. They prove inadequate understanding of their habitat.

Agents who, more often than not, effectively predict the pattern of consequences of their own behaviors learn they can rely on their own predictions and become self-directed. Self-directors have brought their agency under self-control. They can, given their habitat, safely self-decide and can become effective co-creators and autonomous actors.

Self-directors are fully autonomous agents who truly self-maintain their existence (while being embedded in and dependent on a habitat to which they contribute). They prove they generally understand the consequences of their own actions and hence tend to appraise the habitat as safe and full of opportunities. They are mostly co-creating and they themselves are the authority of their life. They exhibit an internal locus of control and are self-optimizing their life. In general they are happy.

Agents who often fail to predict the consequences of their own behaviors live in a world of random outcomes. When they self-decide, they are more often than not confronted with unforeseen, typically negative outcomes that they cannot couple to their own actions.

Since they often cannot rely on their own decision-making to realize intended benefits, they fall back and rely on social mimicry, which externalizes their locus of control.

In general they appraise the habitat as unsafe and problematic. This activates undirected anxiety (associated to the state of the whole habitat, not at something in it), and they are mostly coping.

So depending on the ability to deal with habitat demands, the habitat is either appraised as safe and opportunity filled or as unsafe and problematic4.

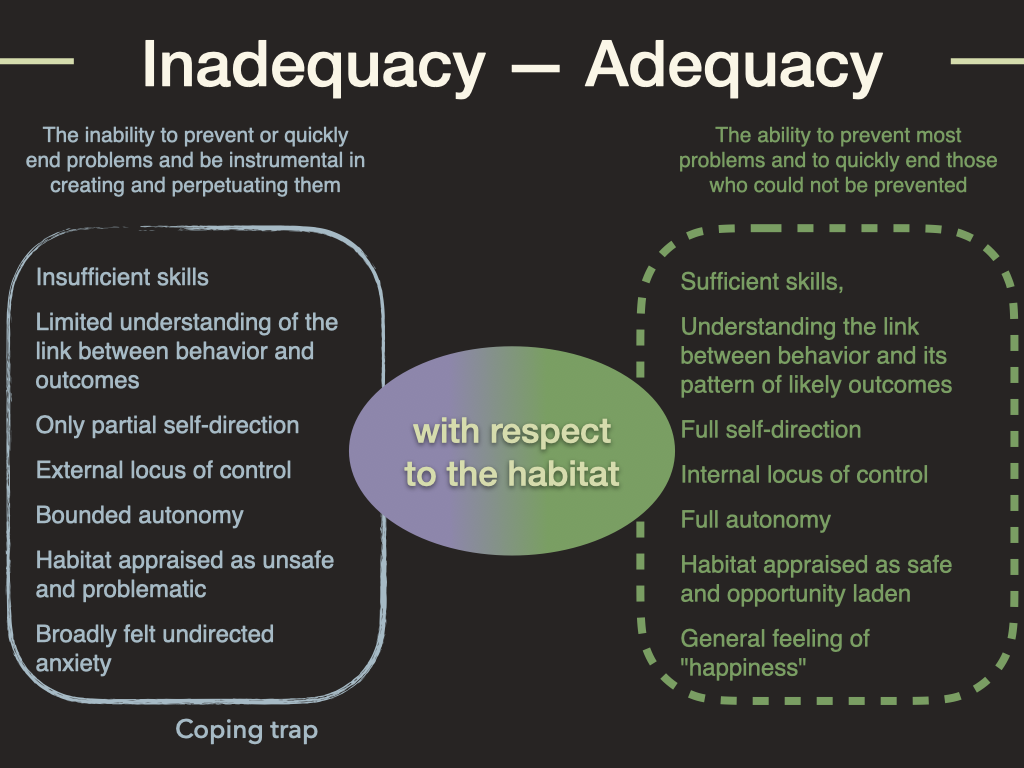

We define adequacy as the proven competence to prevent most problems and to quickly and effectively solve those who could not be prevented. Adequacy is always defined with respect to the habitat. Adequacy in one habitat does not entail adequacy in another.

Adequacy is not some immutable biological fact like species, race, or gender, it depends on a combination of habitat demands, the skill repertoire, a developed sense of realism, appraised safety, and other features that can all to some extend under agentic influence.

Adequacy is an expression, as a pattern of behaviors, of mostly successful real-world interactions. Inadequacy is an expression of an ontology of behavior is response to minimal real-world success5. This text gradually develops some features of these two ontologies6.

The more skills are generalized, they become effective in a wider range of habitats and over longer time-scales. Opportunity exploration and participatory engagement with the habitat, characteristics of co-creation, promote this7.

We refer to adequacy with respect to the habitat as the combination of

In short adequacy is the ability to prevent most problems, and to quickly end those who could not be prevented.

Similarly, we refer to inadequacy with respect to the habitat as the combination of

In short, inadequacy is the inability to prevent or quickly end problems and be instrumental in creating and perpetuating them. We refer to this as a coping trap.

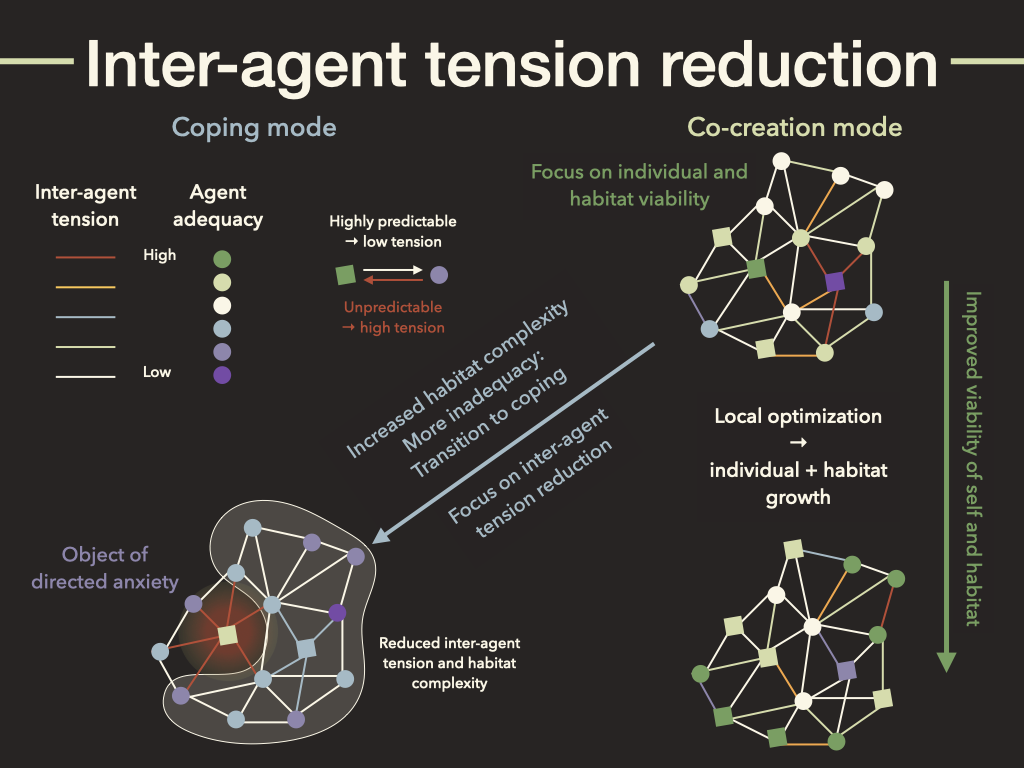

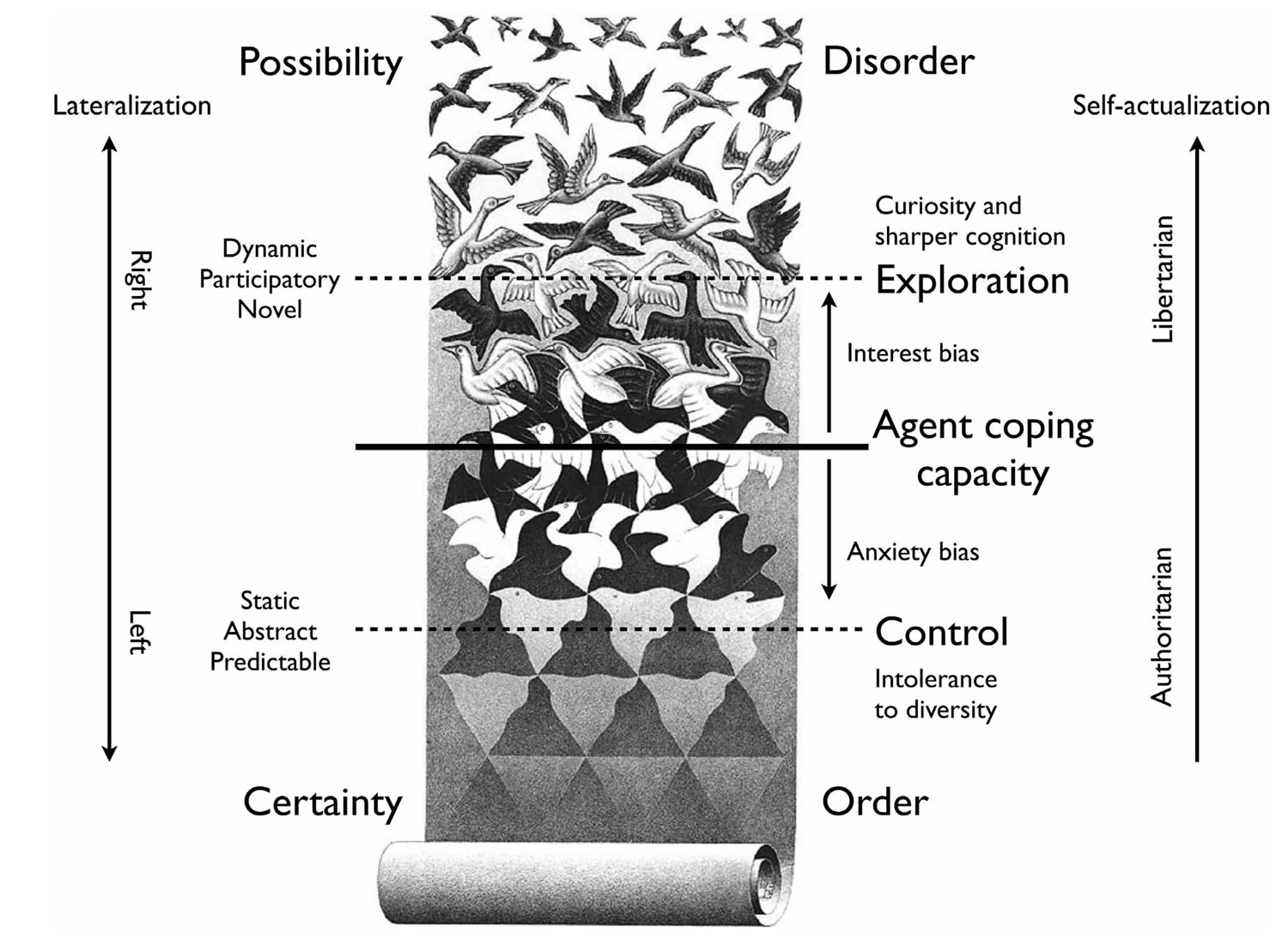

Agents are sources of behavior and the behaviors of many indepently acting agents denotes an explosion of habitat complexity8. Habitat complexity is a challenge for all agents, but most to the least skilled. The appraisal of habitat complexity activates complementary motivations in adequate and inadequate agents.

Adequate agents perceive many affordances and are motivated to explore habitat opportunities and they enhance and protect viability of self and the broader habitat. For the adequate complixity is a resource.

In contrast, inadequacy leads to a focus on the restoration of adequacy. And given the root cause of inadequacy – a lack of understanding between behavior and habitat outcome – this motivates agents to make the habitat more predictable (again). This manifests as an urgency to reduce the unpredictability of the habitat. And since self-directed agent activities are the main source of habitat complexity, inadequacy manifests at intolerance to ill-understood diversity.

The associated behavioral strategy is to focus is on the control or removal of sources of diversity and in particular all co-creation strategies that exceed the inadequate’s scope of understanding.

Typically, the inadequate appraise the most active and effective co-creators as sources of intolerable diversity to be controlled or removed.

The strong urge to curtail and control the behaviors of others is a characteristic of coping dominance9.

Resistance to behavior curtailment is known as reactance10. It is always in response to the curtailment and usually weaker because the adequate typically have plenty of alternatives.

Within the adequate individual, intolerance to diversity promotes self-curtailing of behavioral diversity by complying with some emerging norm. This norm does not need to be optimal or even sensible, it just needs to lead to a less complex habitat.

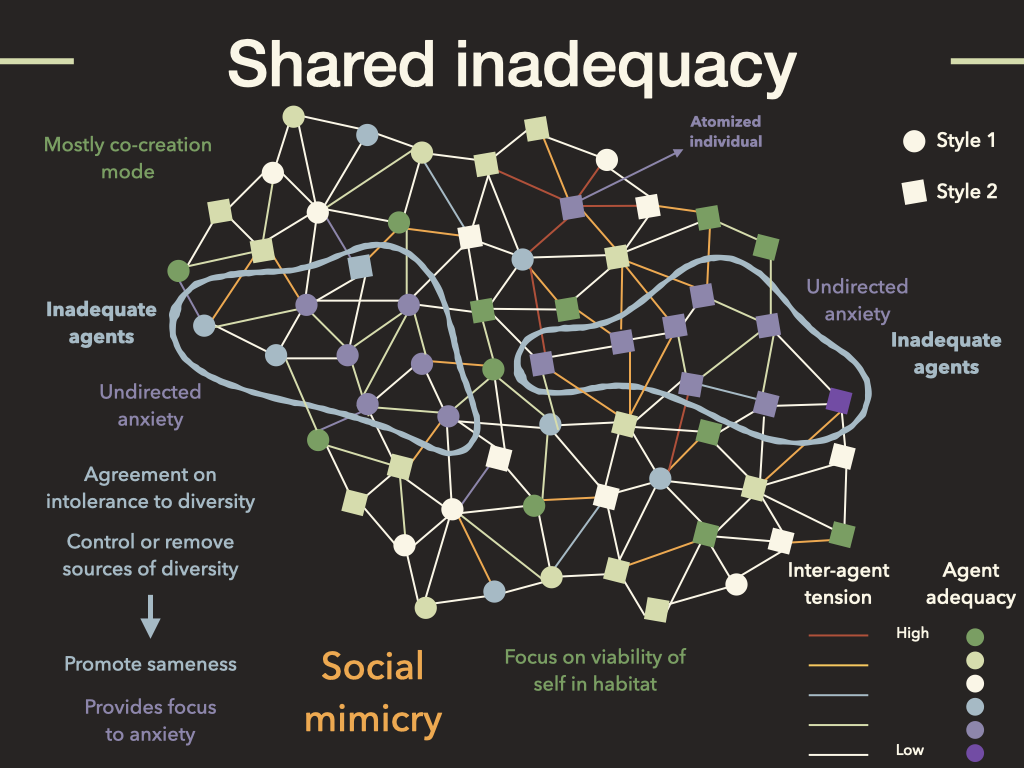

Agents vary not only in adequacy with respect to the habitat. They also form a (never stable and ever-developing) web of relations.

If agents sufficiently understand the link between the actions and the outcome of other agents, inter-agent relations can be tension free and conducive for co-operation. Alternatively, they can be tension laden and conducive for conflict.

In addition, agents differ in interaction styles that we have denoted as style 1 and 2. Given these and other complications, the selection of situationally appropriate behavior is difficult.

Normally, most agents are in a co-creation mode and as such they secure their own viability, while promoting future habitat viability via stigmergy. In doing so, life gradually creates room for more life.

Because co-creating agents focus on viability of self in the habitat, they need to maintain and develop individual adequacy. To a lesser degree they focus on reducing inter-agent tension, because the assumption is that other agents are capable enough to select their own co-creative behavior.

In contrast, inadequate individuals share an urge to reduce habitat complexity to restore or allow individual adequacy. They feel an uneasiness towards the habitat as a whole. This undirected anxiety is so broadly aimed that it is not actionable.

Combined with agent inadequacy and the resulting high risk of harming self and others, this leads to atomized individuals who self-isolate to prevent being victimized by their own adequacy.

However when inadequate agents meet they find the associated reduced behavioral complexity of fellow inadequates attractive. In addition, they share and intolerance to all diversity beyond the scope of understanding.

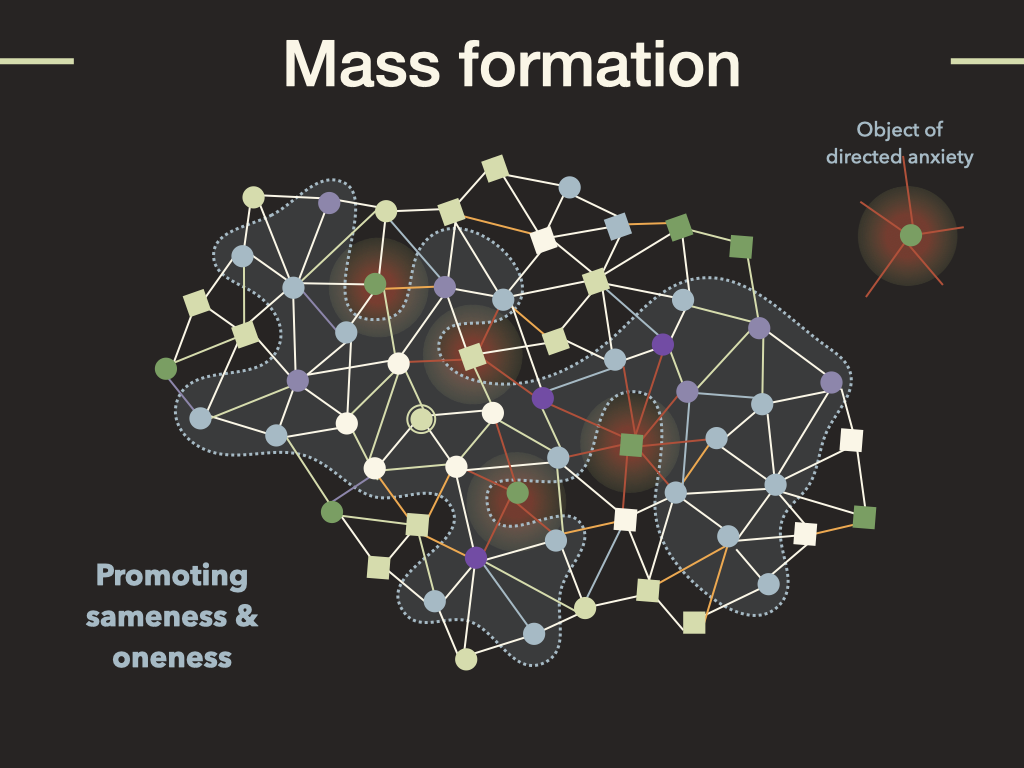

One possible collaborative strategy is to promote sameness by controlling or removing sources of diversity. It is irrelevant what form of sameness is promoted, it is only relevant that it reduces diversity.

This strategy directs the anxiety and makes it actionable as an urge to increase sameness. In addition the collaboration creates a sense of community and purpose that relieves the social atomization and reduces the appraised randomness (and associated meaninglessness) of the world.

This leads to a shared strategy of social mimicry. Since social mimicry starts local, it gives rise to multiple local clusters of agents that each agree on a local form of sameness.

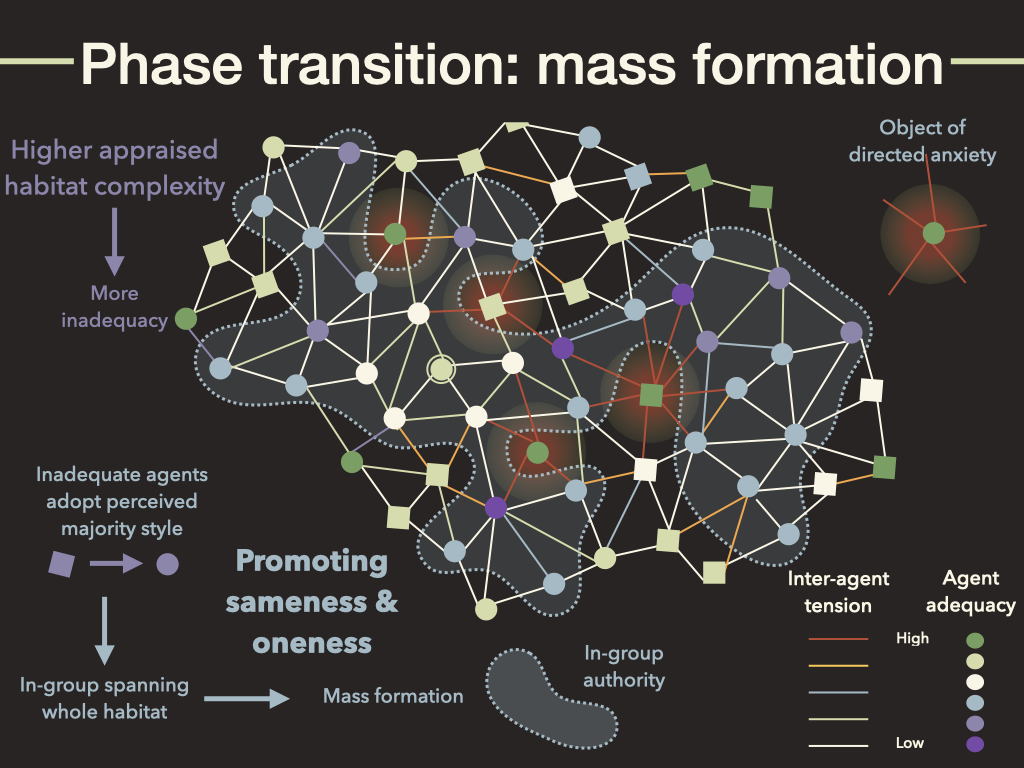

In situations of perceived increased habitat complexity, many agents feel more inadequacy and atomization and transit to the coping mode. This entails a habitat wide strategy shift from self-directed optimization of individual and habitat viability, to strategies focused on reducing habitat diversity and promoting sameness.

In fact, the group-level expression of social mimicry entails a shift to inter-agent tension reduction11. Inter-agent tension is a measure of the unpredictability (perceived randomness) of the behavior of other agents. The more predictable their behavior, the lower the inter-agent tension.

Generally, inadequate agents experience a much higher tension from adequate individuals than vice versa because co-creating agents have higher self-direction and behavioral complexity.

When all group members select from a narrow range of well-known behaviors, within-group tensions are minimized: everyone acts predictably in the eyes of others and behavioral complexity is low12. This effectively reduces the probability of being confronted with one’s inadequacy. But it does not normally improve the habitat.

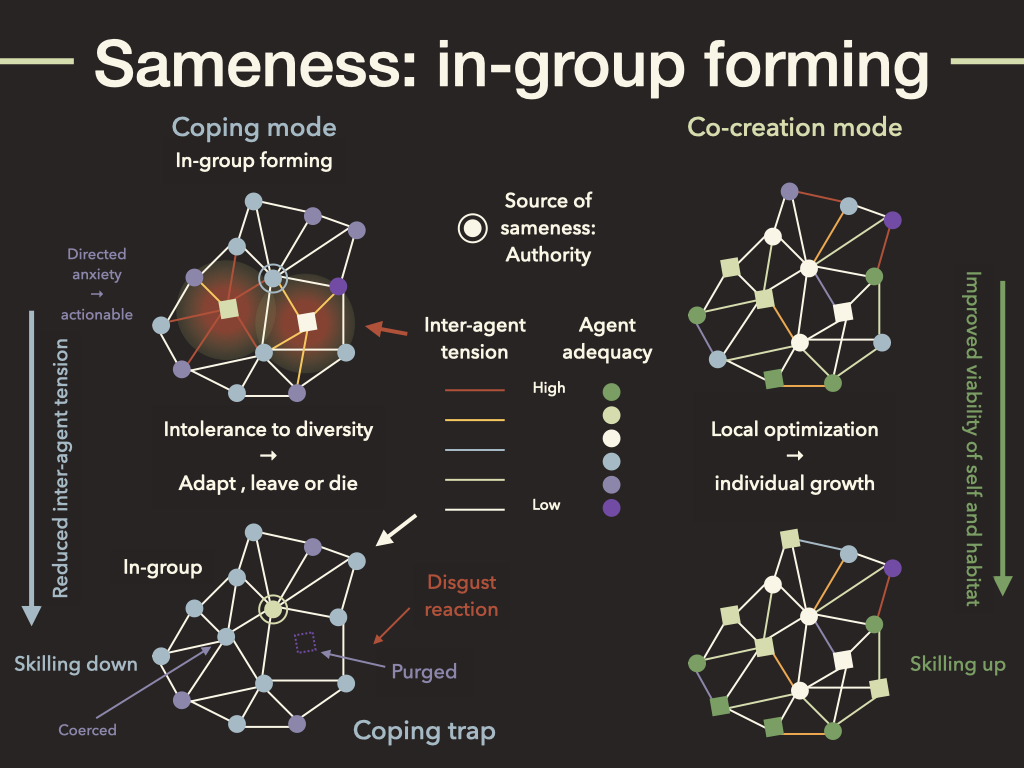

At some point, groups of inadequate copers “surround” adequate self-directors. As a group they are confronted with a source of ill-understood diversity.

This directs both their intolerance to diversity (a strategy) and free-floating anxiety (which determines urgency) to the source of complexity.

The resulting tension between copers and a minority of co-creators resolves when either the co-creator is coerced to limit its overt behavior down to the complexity of group-level shared behaviors or the co-creator is purged. In short, the options are adapt, leave, or die.

The “leave or die” option manifest a ‘disgust reaction’ in the sense of distancing from a toxic, influence that represents no positive value and deserves no protection.

Sameness promotion leads to the formation of an in-group: a group of agents who share similar adequacy limits, who share an in-group specific set of behaviors and motivations, and who behave in in-group specific ways to minimize the frequency of ill-understood diversity.

Within an in-group, the agents who determine the content of sameness most13, have a special position. They are less confronted with their own inadequacy than other members because they decided on the content of their inadequacy evasion strategies.14 The ability to determine the content of sameness makes them authoritative within the in-group.15

Due to the limits that in-group members impose on each other’s behavior, co-creation becomes very difficult, if not impossible. But high-functioning in-group members16 will be less often confronted with their inadequacy, and thus experience markedly reduced anxiety.

Co-creators do not form in-groups. Instead they form flexible communities of freely cooperating individuals that each promote individual short and long-term viability in the habitat context. For that they need to constantly update life-skills and adequacy through participatory engagement with the habitat.

Ironically, the behaviors that help to increase life-skills and lead to individual and habitat growth are also the source of complexity that the inadequate are intolerant to and try to suppress. This entails that in-groups actively counteract the very influences that can improve their quality of life. It locks them in a coping trap with minimal viability.

This also points to a characteristic difference between copers and co-creators: faced with challenges co-creators skill-up, while copers reduce habitat complexity and skill-down in the service of sameness.

The local promotion of sameness leads to the formation of multiple unequal groups that at some point meet. And that leads to tension between two or more unequal in-groups.

Because in-groups base their cognition on the (arbitrary) content of their own sameness17, they are unable to predict the outcomes of the actions of out-groups. The resulting sense of inadequacy directs the copers broadly felt anxiety and activates an urge to reduce the diversity between the two in-groups.

The tension manifests as an unstable balance between incompatible tendencies to:

The tension, and likely overt conflict, persists as long as the differences persist. At some point in time, possibly after conflict and at great costs of in- and out-groups, enlarged and more stable in-group emerges18.

Once this is established the inadequacy associated anxiety becomes undirected again. (Which entails it is free to be redirected to a new source of ill-understood diversity.)

The enlarged in-group has some sameness style that is now adopted by more agents, who in part needed to change their style. This might be a source of future tension.

The in-group can is only remain stable when it sufficiently suppresses emerging or latent diversity within the in-group. This entails that in-groups always need to invest in in-group diversity curtailment19.

Stable authority needs an infrastructure to implement intolerance to diversity (which may also suppresses the benefits of co-creation)20.

And as long as out-groups exists, even as as slightly different subpopulations of the in-group, its authoritative structures need to be ready and able suppress diversity and enlarge oneness21.

In-groups, as authoritative structures, have a natural tendency to grow. And since this holds even when resources can better be used in other ways. This drain on resources eventually precludes further growth and may be harmful22.

This enriches the role of authority: it is not only a sources of a particular sameness, but it also represents the center of an infrastructure that contributes to the stability of the particular sameness that its inadequate members need to prevent being confronted with their inadequacy.

The previous provides insight in the underlying features of authority. Authority is:

At the same time communities of co-creators within a habitat comprising of more skilled, more diverse, and hence unique individuals hardly feel conflict when confronted with another groups of skilled, diverse and unique individuals. They use the added diversity as a resource to enhance the life-skills necessary for a habitat wide local optimization process of each agent in its environment.

The previous assumed that the mass transition from co-creation to coping just happened. The transition process is actually a complex phenomenon similar to what physics refers to as a phase transition (like from liquid to solid).

Different individuals transit at different moments and probably multiple times to and fro before settling in the coping mode. This depending on how the complexity of the habitat is appraised. The higher the appraised complexity (and the lower the adequacy) , the more likely coping becomes24.

Since coping comes with social mimicry, it leads to a positive feedback loop where more and more inadequate agents adopt a perceived majority style. For individuals this might entail some flip-flopping, before discovering the style of the emergent majority.

This mass formation process adopts, ever quicker, most inadequate agents into growing in-groups. At some transition point these coalesce, seemingly in an instant, to an in-group that spans all corners of the habitat. That is the phase transition due to the habitat wide promotion of a single form of sameness and oneness.

The members of the habitat-spanning, but still sparse25, in-group experience tension wherever adequate self-deciders still co-create and hence stand out on the just-created background of sameness. This directs the in-group’s undirected anxiety to the most visible remaining self-deciders.

The remaining self-deciders stall regression towards further uniformity, simplification, and complete habitat dysfunctioning26. So resistance to emerging sameness, while individually dangerous, is essential to preserve part of the previous habitat well-functioning27.

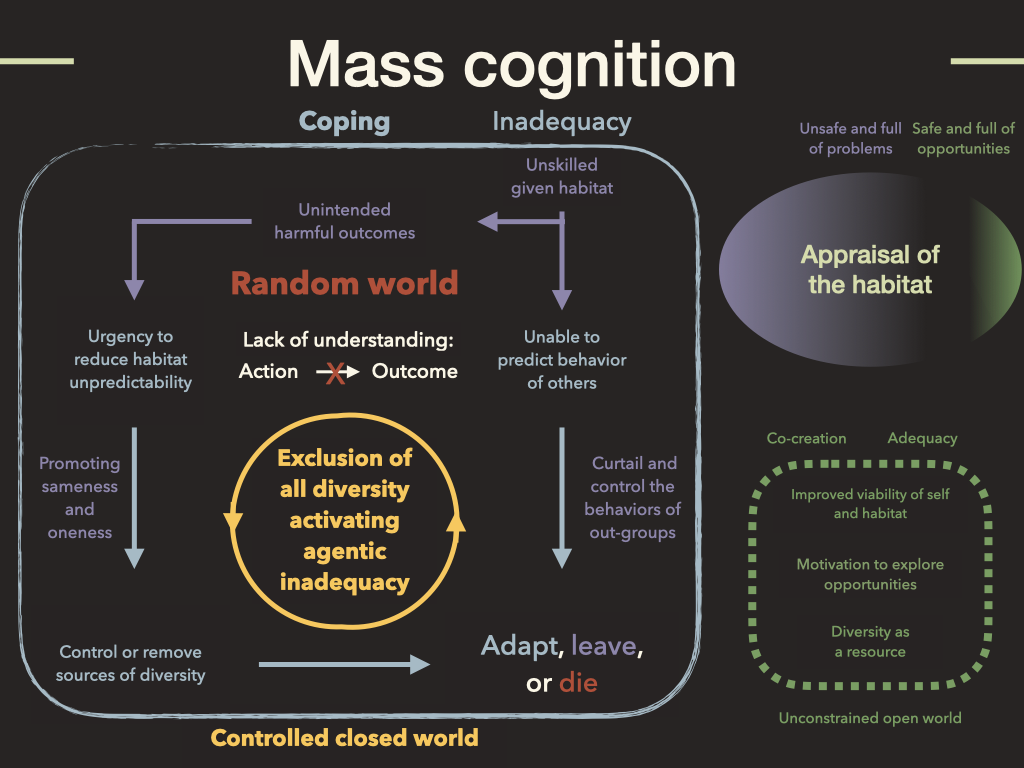

Mass cognition is a group-level manifestation of coping that starts with not having the skills to

The inadequate live in a world with random outcomes where they do not understand the relation between action and outcomes of self and others.

Being unable to prevent unintended harmful outcomes of behaviors activates an urge restore adequacy through reducing habitat unpredictability. This leads to the promotion of oneness and sameness through control and removal of sources of diversity. Out-groups are given the options adapt, leave, or die.

Similarly, the inability to predict the behaviors of others activates an urge to curtail and control their behaviors. Again this leads to the options adapt, leave, or die.

The overall strategy of mass cognition can be summarized as: the exclusion of all diversity activating agentic inadequacy.

This control strategy effectively aims to reduce an unconstrained open world to a controlled closed world that excludes all that freaks out the inadequate[^Safe]. And that is why it gains broad support among the inadequate.

Even during a mass formation event there is still a minority of adequate agents who persist in co-creation strategies, albeit very much curtailed.

For the habitat as a whole this entails that the features of co-creation are minimally expressed. Only few improve and protect the viability of the habitat, few are able and motivated to explore opportunities, and few see diversity as a resource.

During mass formation the habitat is appraised as unsafe, deficient, and full of problems, and only few experience it as safe enough to explore opportunities.

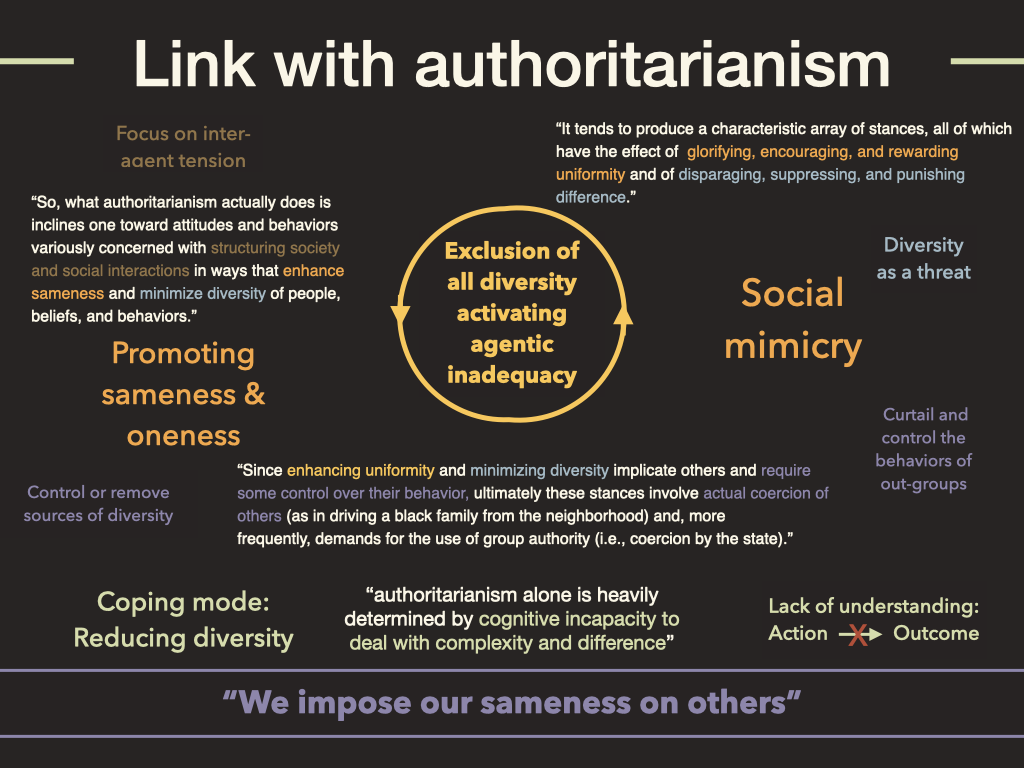

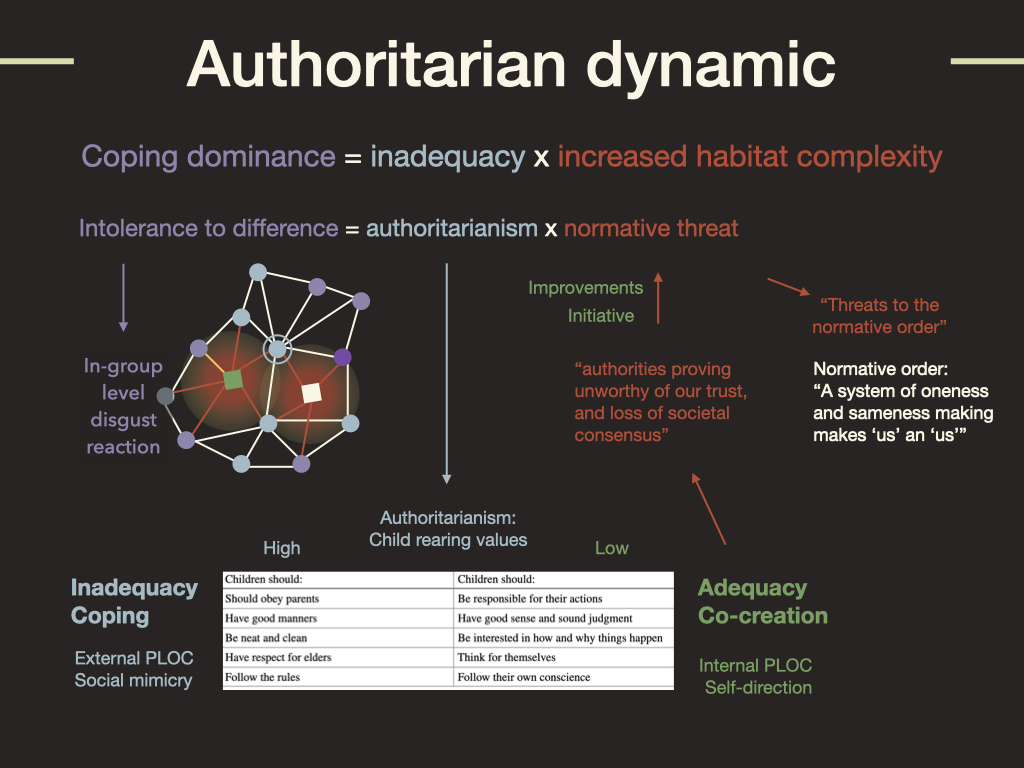

What we have been describing for a general living agent manifests within humanity as “authoritarianism”. And particularly as conceptualized by Karen Stenner in her 2005 book “The Authoritarian dynamic”.

In fact our narrative provides a first principles derivation of the defining features of authoritarianism

Stenner writes:

So, what authoritarianism actually does is [it] inclines one toward attitudes and behaviors variously concerned with structuring society and social interactions in ways that enhance sameness and minimize diversity of people, beliefs, and behaviors.

This refers to “promoting sameness & oneness” and “inter-agent tension reduction”. Stenner continues:

It tends to produce a characteristic array of stances, all of which have the effect of glorifying, encouraging, and rewarding uniformity and of disparaging, suppressing, and punishing difference.

This suggest “social mimicry” as the driver of uniformity. And it indicates that “diversity is a threat”.

In addition:

Since enhancing uniformity and minimizing diversity implicate others and require some control over their behavior, ultimately these stances involve actual coercion of others (as in driving a black family from the neighborhood) and, more frequently, demands for the use of group authority (i.e., coercion by the state).

This bluntly states that sources of diversity must me controlled or removed via curtailing and controlling the behaviors of out-groups.

Stenner also states that:

“authoritarianism alone is heavily determined by cognitive incapacity to deal with complexity and difference”

Which is a way to define ‘inadequacy’.

This all leads to what we refer to as the Authoritarian Motto: “We impose our (arbitrary)29 sameness on others”.

Stenner produced a simple formula to predict the strength of the intolerance to difference.

Intolerance to difference = authoritarianism x normative threat

A normative threat is threat to the normative order. And she defines that as a system of oneness and sameness that makes “us” an “us”. A single out-group enacting some other sameness is annoying, but not really a threat. A true normative threat is something that markedly erodes the in-group’s sameness and inspires in-group members to first mimic it and eventually to self-directedly improve on it.

Stenner specifically mentions authorities proving unworthy of trust and loss of societal consensus. The first leads either to a shift towards other authorities or to more self-direction. The loss of social consensus leads to a more complex world.

To determine whether individuals act as authoritarian or as self-director, Stenner used 5 simple two-option questions about how children should act .

| Children should: | Children should: |

|---|---|

| Obey parents | Be responsible for their actions |

| Have good manners | Have good sense and sound judgement |

| Be neat and clean | Be interested in how and why things happen |

| Have respect for elders | Think for themselves |

| Follow the rules | Follow their own conscience |

The options on the left correspond to an external locus of control and exhibit social mimicry. The options on the right correspond to an internal locus of control and self-direction. Individuals how scored high on the left options are classified as authoritarian.

To an authoritarian a normative threat is anything that self-empowers other agents to mimic less and self-decide more since this leads to a crumbling of the sameness and oneness designed to evade confrontation with one’s inadequacy.

In the absence of normative threats, authoritarians are not intolerant to diversity; a perceived normative threat changes this immediately into an in-group level digust reaction.

A summary of much of the previous is that coping dominance is activated by by a combination of inadequacy and the threat of increased habitat complexity. Typical threats are highly visible self-deciding co-creators – adequate individuals – who inspire and empower others with more effective and more realistic ideas, insights, and activities that benefit the habitat on the short and long term in ways that elude the inadequate.

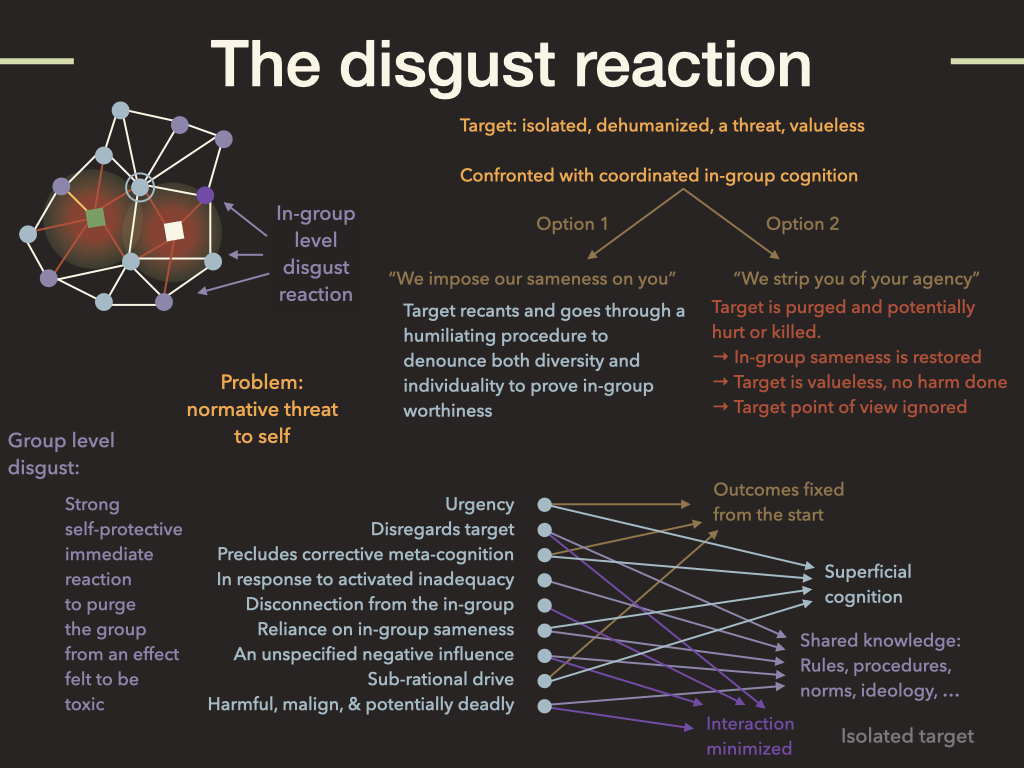

The group-level disgust reaction is in characteristic response to a normative threat that is experienced as a threat to self.

Specifically a group-level disgust reaction a strong self-protective immediate reaction to purge the group from an effect felt to be toxic.

This is a rich description that points towards the main features of the associated decision-making.

This breakdown of the definition of group-level disgust points to the key features the in-group behavior selection:

The target is isolated, de-individualized, and perceived as a valueless threat The target is confronted with two options.

The first option is “We impose our sameness on you”. And the second **“We strip you of your agency”. Options corresponds to adapt, option 2 to or leave or die.

The first option is that the target recants and passes through a humiliating procedure in which it has to denounce its diversity, its individuality, and proof its in-group worthiness30. This option purges the diversity and restores oneness.

When the target is sufficiently self-directed and refuses to be brought down to the demanded sameness, restoration of oneness is impossible. The focus then moves to purging the target.

The way the target understands the habitat and and can engage in skilled behavior represents toxicity. Contact with the target’s point of view must be minimized at all costs. As a toxic influence, the target is valueless, hence no harm is done even if the target is hurt or killed. This restores in-groups sameness.

Much of the background has been published in “Cognition from life” (Andringa et al., 2015), “The Evolution of Soundscape Appraisal Through Enactive Cognition” (van den Bosch et al., 2019), and “Coping and Co-creation: One Attempt and One Route to Well-Being. Part 1 & 2” (Andringa & Denham, 2021). Links to the files in the /basics section ↩︎

Psychology tends to produce a rich and detailed description of the diversity of human behavior. Where psychology provides the ‘what’, core cognition aims to explain ‘why’ these cognitive phenomena exist and ‘why’ they have the properties they exhibit. ↩︎

Fredrickson’s Broaden and Build Theory describes this difference as underlying negative and positive emotions. For example, happiness is a goalless progression of favorable states. It expresses high co-creation and high coping skills. ↩︎

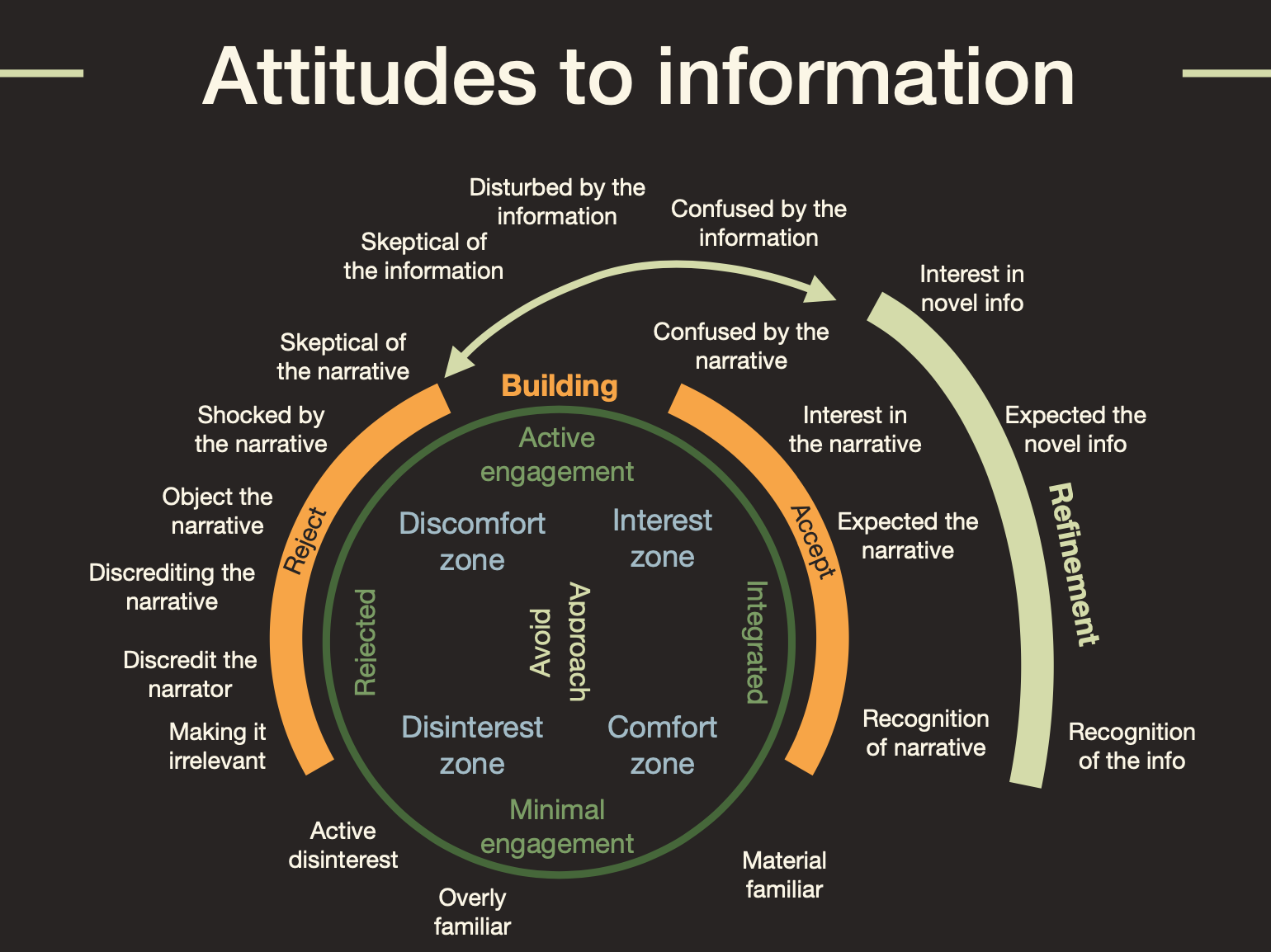

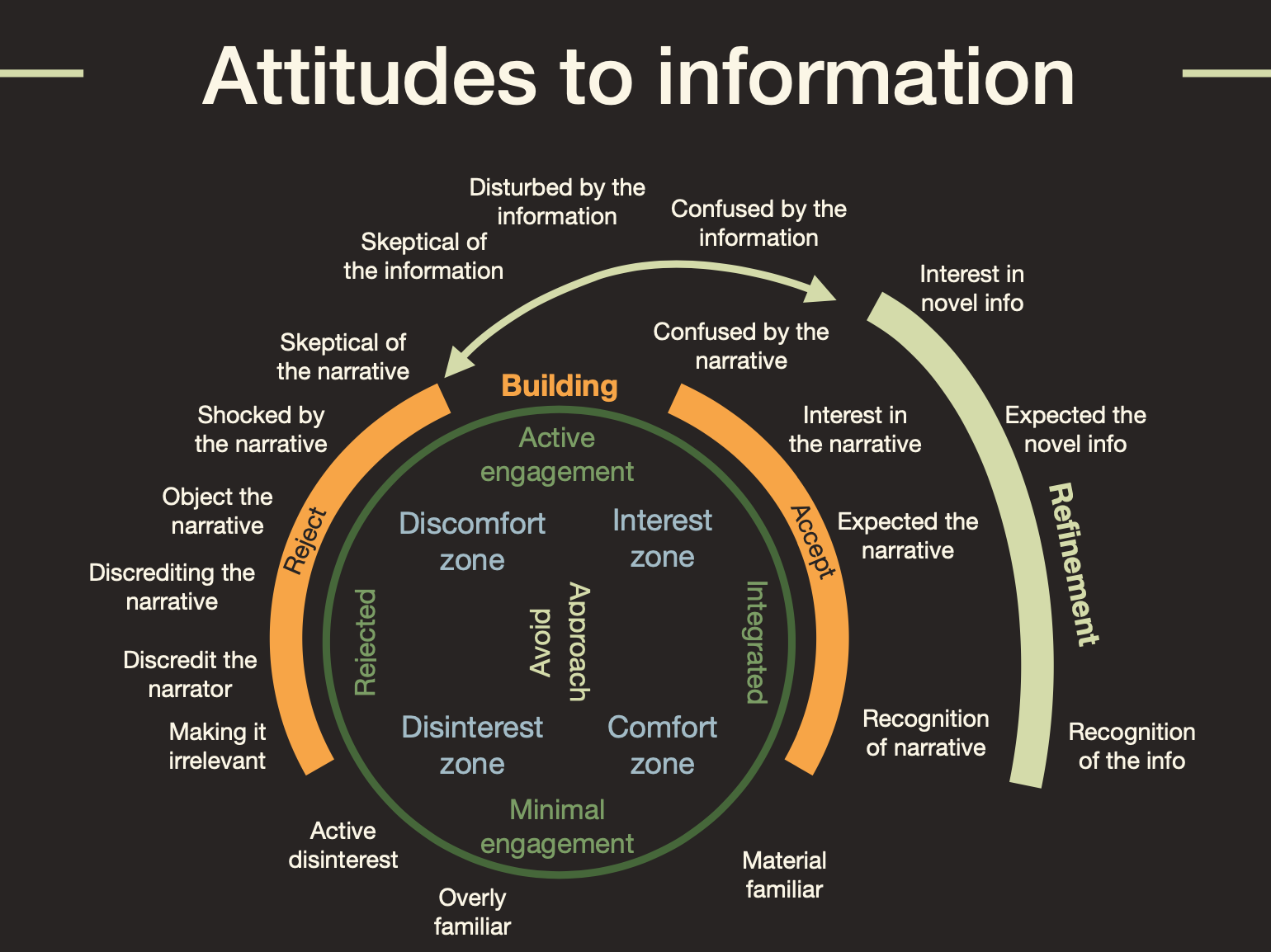

We have described this process in detail for the appraisal of the sonic environment in Table 1 and Figure 4 of van den Bosch et al. (2019) ↩︎

For woke readers who managed to come this far: because adequacy is defined in relation to real-world effectivity, it is completely independent of whether you identify as a particular species, race, or gender, or whether you decide that your skills, ideology, or outlook of the world are effective. Your (in)adequacy is solely determined by the average effectivity of real-world interactions: whether or not your behaviors realize intended outcomes. ↩︎

A more complete development of these behavioral ontologies is available in Andringa&Denham (2021), which is also presented in the /basics section and in summary in Two contrasting ontologies. ↩︎

In Psychology Barbara Fredrickson addressed the Role of positive emotions in What good are positive emotions in what became The Broaden and Build theory. ↩︎

Physicist would measure this interns of entropy: a measure of the number of states the habitat can be in. However a habitat, even a very complex one, is not in any of all possible random states, as a gas of a given temperature would be. Rather the habitat is in any of many highly unlikely (hence unstable) beneficial states that can only be reached through the skilled participation of its comprising agents. ↩︎

This characteristic of coping is via a very powerful phenomenon that we refer to as closing the system and that leads to highly predictable, and for that reason highly useful artifacts such as computers. Probably a very similar “closing the system” processes let to the evolutionary development of multi-cellular tissues and individual. ↩︎

See for example Miron (2006) ↩︎

In physical terms this corresponds to a reduction of the number of the degrees of freedom, an entropy reduction in the habitat, and a reduction of temperature. Co-creation is “hotter” than coping. Copers prefer a reduction of temperature. ↩︎

This is similar to the transition from free-flowing water to crystalline ice (ice can still flow, albeit much slower and in response to much higher pressures). Another temperature dependent phase transition is associated with the Curie temperature of ferromagnetic metals. These metals can only be magnetized below their Curie temperature. Mass formation is a special group-level phenomena that occurs only due to a reduction of the degrees of freedom (temperature). ↩︎

In modern parlance these could be called ‘influencers’. ↩︎

In social justice jargon this would be referred to as ‘privilege’. ↩︎

This might be the reason who media control is key to oligarchic control. ↩︎

Soviet citizens referred to these as apparatchiks. ↩︎

Many so-called political analysts demonstrate this feature blatantly obviously by failing to represent the position of some out-group and basing their “analysis” solely on the in-groups understanding of the out-group. The result makes full sense to the in-group, but is a waste of words in terms of realism. ↩︎

Wars, globalization, and mergers & acquisitions in business are examples of this. Unipolar global governance and monopolies are the natural end-points of enlarging the in-group. ↩︎

In humans this is for example expressed as rules, norms, laws, standards, procedures, propaganda, ideologies, advertising, career-paths, and the associated infrastructure such as law enforcement, media, and schools systems to ensure that most individuals end up contributing to “oneness and sameness”. ↩︎

In our societies this is implemented as the security state: intelligence agencies, security forces, and internal propaganda outlets. ↩︎

This is why authorities in extreme circumstances turn their diversity suppression to the own in-group (as with the Jacobins and Stalin’s Great Purge). ↩︎

Imperial overstretch is the tendency of all empires to grow beyond its sustainability limits so that at some point in time the military and other infrastructure for further growth becomes detrimental to the existence of the empire. ↩︎

“… it seems that the bureaucratic form of organization stultifies the functioning of highly autonomous and motivated employees, while it actually provides the less autonomous employees guidance and effectiveness in roles in which they would otherwise not be able to function.” (Andringa, 2013, p225) ↩︎

It is a bit more complicated than this. We (Van den Bosch et al., 2018) wrote a paper the appraisal of the sonic environment that outlines appraisal in more detail (Figure 4 and Table 1). ↩︎

Initially the shape of the habitat-wide in-group is more a sponge or Swiss cheese than a coherent block. The co-creators are still active in the holes. ↩︎

In the movie Brasil the only capable technician who makes unsanctioned repairs in a dysfunctional bureaucracy is treated a “terrorist”. ↩︎

Humans have concurrent coping and co-creation abilities, even when coping is dominant, co-creation logic is perceived. Co-creation examples balance the drive for further coping and can hence block further societal degradation. ↩︎

This is actually a definition of out-groups: an out-group is any agent (or group) whose behavior is not understood. ↩︎

The reason to stress the arbitrary nature of the “sameness” is that it is rooted in complexity reduction and not in the realization of broad benefits. The structures of co-creation (usually only dynamically stable through continual care of self-directed co-creators) are rare beneficial states in a possibility space that is vastly bigger than the simplified and impoverished state-space of sameness and oneness that offer only the benefit of low complexity. ↩︎

A fascinating example of such a humiliating procedure (ceremony almost) was recorded in during the Evergreen events in 2018 that led to the purging of Brett and Heather Weinstein. Embarking on the canoe towards equity stands for the reduction of diversity. Some individuals had to ask for permission for boarding the canoe by pledging their loyalty to the equity goals and denouncing their uniqueness. https://youtu.be/FH2WeWgcSMk?t=858 ↩︎

Very short intro to core cognition.

Core Cognition is the cognition shared by all of life. Core Cognition describes the basic decision making structures that allowed living agents to grow a biosphere from small and fragile to extensive, robust, incredibly diverse, and highly efficient. Core cognition describes the processes of behavior selection for survival and thriving, which is something that is relevant for all of living individuals: from bacteria to humans. But cognition for flourishing – coping – is essentially different from the cognition for survival – co-creation. This website addressed the power and consequences of this basic distinction and we argue that also human cognition (psychology) manifests core cognition in all its key properties.

Update: The first part of mass formation serves as a more concise introduction to core cognition. This text is yet another application of core cognition.

The 4 texts in this section are based on a recent paper (Andringa & Denham, 2021) in which we describe the basics of core cognition starting from the demands to being and remaining alive and maximizing viability of self and habitat. In it we derive core cognition and its two main modes, coping and co-creation, from first principles. We apply this by explaining the structure of personality and by explaining why two completely different approaches to social well-being can emerge.

With this text come two summary tables:

These texts are based on the original published version, but will deviate over time. The original version can be found here:

A combined pdf can be found here

A number of other texts are also relevant.

Andringa, T. C., Bosch, K. A. M. van den & Wijermans, N. Cognition from life: the two modes of cognition that underlie moral behavior. Frontiers in Psychology 6, 1–18 (2015).

Andringa, T. C., Bosch, K. A. M. van den & Vlaskamp, C. Learning autonomy in two or three steps: linking open-ended development, authority, and agency to motivation. Frontiers in Psychology 4, 18 (2013).

Andringa, T. C. & Angyal, N. The nature of wisdom: people’s connection to nature reflects a deep understanding of life. Psychology. Journal of the Higher School of Economics 16, 108–126 (2019).

Bosch, K. A. M. van den, Welch, D. & Andringa, T. C. The Evolution of Soundscape Appraisal Through Enactive Cognition. Frontiers in Psychology 9, 1–11 (2018).

Andringa, T. C. The Psychological Drivers of Bureaucracy: Protecting the Societal Goals of an Organization. in Policy practice and digital science : integrating complex systems, social simulation and public administration in policy research 221–260 (Policy Practice and Digital Science, 2015). doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12784-2_11.

This 4 section series is based on a recent paper (Andringa & Denham, 2021) in which we outline the basics of core cognition starting from the demands to being and remaining alive and maximizing viability of self and habitat. In it we derive core cognition and its two main modes, coping and co-creation, from first principles.

A living entity is different from a dead entity because it self-maintains this difference. To live entails self-maintaining and self-constructing a “far from equilibrium state”. The work of Prigogine (1973) showed that, for thermodynamic reasons, such an inherently unstable system can only be maintained via a continual throughput of matter and energy (e.g., food and oxygen). Death coincides with the moment self-maintenance stops. From this moment on, the formerly living entity moves towards equilibrium and becomes an integral and eventually indistinguishable part of the environment.

A living entity “is” — exists — because it “does”: it satisfies its needs by maintaining the throughput of matter and energy by “adaptively regulating its coupling with its environment so that it sustains itself” (Andringa et al., 2015; Barandiaran, Di Paolo, & Rohde, 2009 p. 8). An autonomous organization that does this is called a “living agent” or an agent for short (Barandiaran et al., 2009). Note that we refer to an agent when the text pertains to life in general and is part of core cognition. Where we specifically refer to humans we use the term “person”. The term “individual” can refer to both, depending on context.

Life is precarious (Di Paolo, 2009), in the sense that it must be maintained actively in a world that is often not conducive to self-maintenance and where both action and inaction can have high viability consequences (including death). We refer to behavior as agent-initiated context-appropriate activities with expected future utility that counteract this precariousness and minimize the probability of death. Behavior is always aimed at remaining as viable as possible, since harm — viability reduction — can more easily end a low-viability than a high-viability existence.

A pattern of behaviors that effectively optimizes viability leads to flourishing, while a pattern of ineffective or misguided behaviors leads first to languishing and eventually to death. Life is “being by doing” the right things (Froese & Ziemke 2009, p. 473). Viability is a holistic measure of the success or failure of “doing the right things”, since it is defined as the probabilistic distance from death: the higher the agent’s viability, the lower the probability of the discontinuation of life. A walrus that falls off a cliff may be perfectly healthy, but it has zero viability, since it will die the moment it hits the ground. While healthy, it is in mortal and inescapable danger, and hence unviable. In general, threat signifies a perceived reduction of contextappropriate behavioral options that allow the agent to survive. Maximizing viability (flourishing) and minimizing danger (survival) constitute basic motivations of life. In fact, we call any system cognitive when its behavior is governed by the norms of the system’s own continued existence and flourishing (Di Paolo & Thompson, 2014). This is also a reformulation of “being by doing”.

Agency entails cognition: behavior selection for survival (avoiding death) and thriving (Barandiaran et al., 2009) (optimizing viability of self and habitat). We have argued that cognition for survival is quite different from cognition for thriving (Andringa et al., 2015). Cognition for survival is aimed at solving problems, where a problem is any perceived threat to agent viability, interpreted as a pressing need that activates reactive behavior. We called this form of cognition coping. In humans, (fluid) intelligence is a measure of problem-solving and task-completion capacity and manifests coping. The objective of coping is ending/solving the problems that activated the coping mode, so ideally coping is a temporary state. We refer to the problem-solving ability, including successful test and task completion ability (Gottfredson, 1997; van der Maas, Kan, & Borsboom, 2014), as intelligence.

However, when the agent’s problem solving is inadequate and problems are not solved and are potentially worsened or increased, the perceived viability threat remains activated and the agent is trapped in the coping mode of behavior. A coping trap keeps the agent in continued threatened viability, and hence in behaviors aimed at short-term self-protection in suboptimal states that are far from flourishing. Maslow (1968) calls this deficiency (D) cognition, since it is ultimately activated by unfulfilled needs. It is a sign that the intelligence of the agent failed to end (solve) problem states.

While the coping mode of behavior is for survival, the co-creation mode is for flourishing. Successful coping leads to solved problems and satisfied needs, and hence to its deactivation. Therefore, co-creation is the default mode of cognition and coping is — ideally — only a temporary fallback to deal with a problematic situation. Continued activation is the success measure of the co-creation mode and avoiding problems (or dealing with them before they become pressing) is, therefore, the main objective of co-creation. It is essentially proactive behavior (thus not just “proactive coping”, since successful coping leads to its deactivation). Maslow (1968) refers to co-creation as being (B) cognition, and we described it as pervasive optimization and “generalized wisdom”, for reasons which will become apparent. The objective of co-creation is pro-actively producing indirect viability benefits through self-guided habitat contributions that improve the conditions for future agentic existence.

This is known as stigmergy: building on the constructive traces of past behaviors left in the environment (Doyle & Marsh, 2013; Gloag et al., 2013; Heylighen, 2016b; 2016a) and that, in the aggregate, gradually increase habitat viability. This expresses authority as a shaping force in the habitat (Marsh & Onof, 2008), via influencing others through habitat contributions. Habitat is defined as the environment from which agents can derive all they need to survive (and thrive) and to which they contribute to ensure long-term viability of the self and others.

Habitat viability is a measure of the potential of the habitat to satisfy the conditions for agentic existence (i.e., satisfied agentic needs). For example, a habitat can be deficient in the sense that its inhabitants continually have unfulfilled needs (and hence are in the coping mode). The habitat can also be rich, so that pressing needs can easily be satisfied and co-creative contributions can perpetuate and enhance habitat viability.

The biosphere grew from fragile and localized to robust and extensive, so we know beyond doubt that life on Earth is, in the aggregate, a constructive force. It is the co-creation mode’s contributions to habitat viability that explain this. In fact, the biosphere can be seen as the outcome of stigmergy: the sum total of all agentic traces left in the environment since the origin of life (Andringa et al., 2015). Co-creation and generalized wisdom as the main cognitive ability drive the biosphere’s growth and gradually increase its carrying capacity: the sum total of all life activity in the biosphere. This makes co-creation the most authoritative influence on Earth. Coping is also an important authoritative influence, but it is limited to setting up and maintaining the conditions for pressing need satisfaction.

Figure 1 presents the co-dependence of acting agents on their habitat. The habitat comprises the aggregate of agentic activities, but is not an actor itself. Hence, a viable habitat is composed of the sumtotal of previous co-creative agentic traces that form a resource to satisfy the conditions on which current agentic existence depends. This entails that, signified by the question marks, agents should be aware not only of their own viability, but also of habitat viability. In fact, we have argued (Andringa, van den Bosch, & Weijermans, 2015) that early, primitive life forms were yet unable to separate self from the co-dependence of self and habitat. This leads to an “original perspective” on the combined viability of agent and habitat, which allowed their primitive cognition to optimize the whole, while addressing selfish needs and creating ever better conditions for agentic life. This can be termed pervasive optimization and it expresses an emergent purpose of life on Earth to produce more life. Albert Schweitzer (1998) formulated a slightly weaker version of this “I am life that wills to live in the midst of life that wills to live.”

Pervasive optimization is the driver of well-being. We propose that successful well-being, with a focus on ‘being’ and hence interpreted as a verb, can best be understood as a co-creation process leading to high viability agents, increased habitat viability, and long-term protection and extension of the conditions on which existence depends.

The two modes of behavior have quite different impacts on the habitat and, by extension, the biosphere. The coping mode is aimed at protecting and improving agent viability with whatever means the agent has access to. Since the objective is avoiding death, the motivation is high, which entails that habitat resources can be sacrificed for self-preservation purposes. Inadequacy can be defined as the tendency to self-create, prolong, or worsen problems that keep an agent in the coping mode. When a habitat is dominated by inadequate agents, as is characteristic of a social level coping trap, habitat viability cannot be maintained, let alone increased. From the perspective of coping, life is at best a zero-sum game.

Alternatively, adequacy can be defined as the ability to avoid problems or end them quickly so that coping is effective and rare. Now co-creation is prevalent so that habitat viability is protected, carrying capacity increases, and long-term need satisfaction is secured. Co-creation is, like the term suggests, a more than zero sum game. This is, as argued above, the true basis of well-being. Due to its lack of “co-creation”, coping protects lower levels of well-being and, at best, resolves (or otherwise takes care of) viability threats (in the sense of removing symptoms of low well-being), while co-creation allows both agent and habitat flourishing.

The inadequacy-adequacy dimension might underlie the proposed single dimension of psychopathology termed p (Lahey et al., 2012; Caspi and Moffit, 2018). This has been conceptualized as “a continuum between adaptive and maladaptive functioning”, “successful versus unsuccessful functioning”, a disposition for negative emotionality or impulsive responsivity to emotion, and unrealistic thoughts that manifest in extreme cases as delusions and hallucinations (Smith et al., 2020). All descriptions fit with our interpretation of inadequacy as the tendency to self-create, prolong, or worsen problems and adequacy as the ability to avoid problems or end them quickly.

Welzel and Inglehart (2010) argue, from the perspective of cultural evolution, “that feelings of agency are linked to human well-being through a sequence of adaptive mechanisms that promote human development, once existential conditions become permissive”, which is a formulation of the dynamics of Figure 1. They argue that “greater agency involves higher adaptability because for individuals as well as societies, agency means the power to act purposely to their advantage”. This uses the concept of agency as a measure of the ability to self-maintain viability, which is related to adequacy.

Living agents, per definition, need to express behavior to perpetuate their existence. And with every intentional action, the agent implicitly relies on the set of all that it takes as reliable (i.e., true in the sense of reflecting reality as it is) enough to base behavior on. We refer to this set as the agent’s worldview. A worldview should be a stable basis, as well as developing over time because it is informed by the individual’s learning history. An agent’s worldview informs its appraisal of the immediate environment. This may be an appraisal of its viability state: whether the habitat is safe or not, or whether it judges the current situation as manageable, too complex, or opportunity filled.

These are basic appraisals shared by all of life that seem to be reflected in the psychological concept of core affect (Russell, 2003). Core affect is a mood-level construct that combines the axis unpleasureable-pleasurable with an arousal axis spanning deactivated to maximally activated. It is intimately and bidirectionally linked to appraisal (Kuppens, Champagne, & Tuerlinckx, 2012; van den Bosch, Welch, & Andringa, 2018) and refers directly to whether one is free to act or forced to respond: whether one can co-create proactively or has to cope reactively. Hence appraisal is a worldview-based motivational response to the perceived viability consequences of the present state of the world. It is motivational, but not yet action. As such appraisal resembles Frijda’s (1986) emotion definition as ‘action readiness’. Which fits with the notion that all cognition is essentially anticipatory:

“Cognitive systems anticipate future events when selecting actions, they subsequently learn from what actually happens when they do act, and thereby they modify subsequent expectations and, in the process, they change how the world is perceived and what actions are possible. Cognitive systems do all of this autonomously.” (Vernon 2010, pp. 89).

The anticipation of the development of the world (comprising of self and environment) refers back to what we earlier introduced as the “original perspective” on the combined viability of agent and habitat, which allowed the first life forms to optimize the whole, while addressing selfish needs and creating ever better conditions for more agentic life. Core affect is a term adopted from psychology (Russell, 2003) that we here generalize to all of life. Core affect is a relation to the world as a whole and not a relation to something specific in that world. Like moods, core affect does not have (or need) the intentionality (directedness) of emotions and it is, unlike emotions, continually present to self-report (van den Bosch, Welch, & Andringa, 2018).

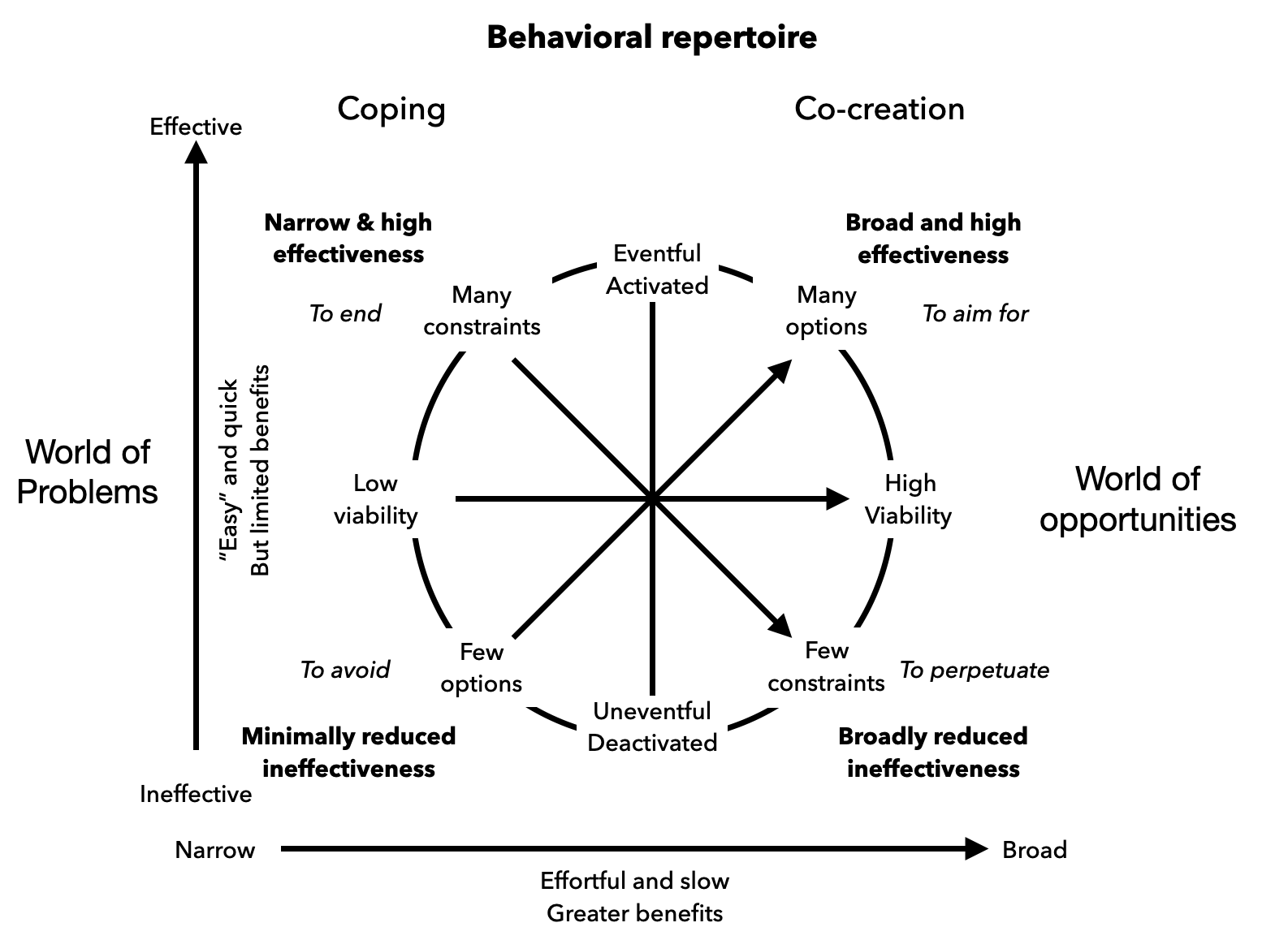

The human worldview is, of course, filled with explicit and shared beliefs, opinions, facts, or ideas interpreted with and filtered by experiential knowledge. This worldview informs whether the situation is deemed dangerous or not (whether avoidance or approach is appropriate). This holds also for a general agent: when the agent judges the situation as safe it can express unconstrained natural behaviors since it has to satisfy few constraints. If the situation is safe and opportunity-filled, it can be interested and learn. But if the situation imposes many constraints, it tries to end these by establishing control. And in a deficient environment the agent is devoid of opportunities (which in humans may correspond to boredom or, in case of lost opportunities, sadness). Core affect then is expressed as motivations to avoid or end (coping) or motivations to perpetuate or to aim for (co-creation). We have depicted this in Figure 2.

Appraisal of reality refers to the behavioral consequences of the current state of the world and it is a form of basic meaning-giving that activates a subset of context appropriate behavioral options (van den Bosch, Welch, & Andringa, 2018). This leads to motivation as being ready to respond to the context appropriately. We define the set of all possible – appraisal and worldview dependent – behaviors as the behavioral repertoire. The richer the behavioral repertoire, the more diverse context appropriate behaviors the agent can exhibit. The more effective its behavioral repertoire, the more effective it becomes in realizing intended outcomes and the more adequate the agent is. Conversely, the less effective the context-activated behaviors, the more inadequate the agent is. Learning either reduces the ineffectiveness of behaviors or it expands the behavioral repertoire.

Expanding the repertoire results from an individual discovery path through a representative sample of different environments and interactive learning opportunities. Broadening is effortful and potentially risky but ultimately rewarding. Fredrickson’s (2005) broaden and build theory fits here by proposing that positive emotions – indicating the absence of problems and hence co-creation – help to extend the scope of behavioral options. This type of learning leads to individual skills that are, through the individual discovery path, difficult to share. This manifests in humans as implicit or tacit knowledge (Patterson et al., 2010) and well-developed agency.

Reducing the ineffectiveness of behaviors is essential in problematic (coping) situations. This may entail adopting, through social mimicry, the behaviors of (seemingly) more successful, healthy, or otherwise attractive agents. The adoption of presumed effective behaviors manifests shared knowledge. Mimicry is a quick fix and works wherever and as long as the adopted behaviors are effective. As a dominant learning strategy, mimicry leads to a coordinated situation of sameness and oneness. The coordinated agents make their adequacy conditional to the narrow set of situations where the mimicked behaviors work. These agents may be intolerant to others who frustrate sameness and oneness. They may express this intolerance by selecting behaviors that enforce social mimicry on non-mimickers. The more they feel threatened, the more they feel an urge to restore the conditions for adequacy and the more intolerant to diversity they are. In humans this is expressed as the authoritarian dynamic (Stenner, 2005).

This discourse leads to a selection of core cognition key concepts with definitions.

This section addresses the quite different and complementary features of coping and co-creation. We need both, because successful coping maximizes time for co-creation. The complementarity of the two modes, as two separate ontologies that disagree on many aspects, might be the root of life’s resilience.

This section addresses the quite different and complementary features of coping and co-creation. We need both, because successful coping maximizes time for co-creation. The complementarity of the two modes, as two separate ontologies that disagree on many aspects, might be the root of life’s resilience. Where resilience is defined as “the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedbacks” (Walker et al., 2004). We originate resilience in the agent’s ability to anticipate and predict.

Coping and co-creation are abilities – in psychology, skills and tacit knowledge (Patterson et al., 2010) – expressed as behavior in response and appropriate to how the agent appraises its habitat context. Of course, agent-initiated actions change the habitat state to which other agents may respond, which, in turn, changes the habitat state. Since the habitat may change even without direct agentic influences, agents exist in an evolving world in which they must position themselves to protect and enhance self and habitat viability. To exist in such an environment, the agent needs anticipatory models (Vernon, 2010) of the state of self and the habitat. It must update these actively, and choose its behavior to realize benefits to self and the habitat. In this open environment, even the best agent generated model leads only to partial predictability. Coping and co-creation strategies increase partial predictability, but use different strategies and complementary logics.

Coping makes the world more predictable by reducing its complexity and creating systems (of agents or objects) with more predictable behavior that bring threats-to-self under control – which requires energy, resources, and continual maintenance – and promote security. The coping mode’s goal is to end perceived viability threats, and coping success entails the discontinued need for its activation. Hence, it is goal-oriented (like problem-solving and task execution) and endowed with a sense of urgency to avoid (further) viability deterioration that justifies the exploitation of previously created viability. Any deviation from manageable order – unfamiliar events or deviant agent behavior – is seen as an unwanted intrusion to be counteracted. Hence, coping leads to an effortfully controlled environment that minimizes unpredictability and diversity. If the threat level – i.e., the expected negative viability impact – increases, so does the drive to suppress diversity.

Since coping is goal-oriented and intends to reduce complexity, it favors shared rules (in general shared knowledge) and behavioral mimicry. The more agents follow the same rules with great precision, the more predictable agents and the habitat become. Coping promotes the spread and precise execution of a single set of behavioral rules. And it endorses an urge to correct or suppress any unwanted diversity. This is a form of social mimicry (Chartrand and van Baaren, 2009) that might not only lead to the spread of effective behavior, but also to lead to a “degree of entanglement” (Combs & Kribner 2008, pp. 264), emergent collective behavior (via mimicry or rules), and a group level perspective.

In human societies, bureaucracy, the military, large corporations, and strict manifestations of religions and ideologies are examples of the coping logic. Technology, from very primitive to complex like computers, depict the best of coping by producing precise outputs as long as the physical environment (the tool and its necessary resources) and the user operate within very tight constraints; this entails trained behaviors.

Coordinated agentic behavior, as social mimicry, is endorsed by agents who expect benefits from more sameness and oneness. Agents with similar needs share similar coordination benefits, but that is unlikely for agents with different needs or those with other (even potentially better) strategies. In fact, imposed external coordination might be detrimental. Differences in expected benefits lead to a separation in in-groups and out-groups. An in-group is a group of agents who express a degree of oneness and sameness through social mimicry and hence share adequacy limits, perceptions of what is beneficial, how to realize these benefits, and what endangers realizing these benefits. Out-groups do not share these limits, either because they have other limits or because they are less limited. By violating sameness and oneness, out-groups frustrate coordinated coping in the eyes of in-groups. Note that out-groups might not even know they are assigned to the out-group and might not raise their defenses.

In-groups (as manifestation of coping) see the risk of frustrated coordinated behavior as an existential threat which justifies exploiting or suppressing out-groups and the habitat alike. Habitat and out-group exploitation may activate out-group resistance that makes goal achievement more difficult. So, the better the in-group is able to control out-groups and habitat, the more likely they are to realize intended results. Due to its problem-solving nature, coping manifests “the ability to realize intended outcomes”. Which is Bertrand Russell’s (1938) definition of power. Hence coping behaviors are a manifestation of power generalized to generic agents.

The coping mode’s manifestation of authority is typically power based in the sense that it sets-up habitat conditions for reduced diversity, increased predictability of agent behavior to facilitate intended outcomes, and to bring viability threats-to-self under control (security) . This is known as coercive authority (as opposed to legitimate authority, Hofman et al., 2017). Coercive power, generally (but not necessarily) leads to benefits for the in-group at the detriment to out-groups and the wider habitat: the zero-sum game that in humanity is associated with manifestations of authoritarianism (Stenner, 2005) and the tragedy of the commons (Hardin, 1968).

Co-creation does not reduce complexity, instead it makes the world more predictable by promoting unconstrained natural behavior and easy need satisfaction through promoting and communicating efforts that facilitate and maintain habitat viability. This creates a safe environment where safety is defined as “a situation or state with positive indicators of the absence of viability threats” (van den Bosch et al., 2018). This communicated absence of threats is a logical necessity since an absence can otherwise not be established. The positive indicators of safety – signs of unforced agentic behavior – allow agents in the habitat to co-create without having to be alert for (unexpected) danger. This allows the uninterrupted functioning of a self-organizing network of interacting agents that satisfy needs most naturally, while minimizing negative impacts and promoting coexistence and even collaboration. Human friendships depend on this logic and they have, like all co-creation processes, no stable outcome or goal other than providing a safe context for growth and flourishing.

This is the complement of coordinating other agent’s behavior (which characterizes coping). Unconstrained natural behavior does not need guidance, since the agents do whatever comes naturally and return to this when constraints are lifted. This harmony between what is possible and what comes naturally stabilizes the habitat, leads to more communicated safety, and increases predictability through the reduction of interagent tension that otherwise might activate coping as fallback. Co-creating agents should become aware of the needs of others and what comes naturally to themselves, others with similar needs, others with different needs, and the wider habitat’s dynamics. They have to optimize all in the context of everything else and over all timescales (we referred to this as ‘pervasive optimization’, Andringa et al., 2015), which is a direct reference to Sternberg’s definition of wisdom:

The application of tacit knowledge towards the application of a common good through a balance among intra-, inter-, and extra- personal interests to achieve a balance among adaptation to existing environments, shaping of existing environments, and a selection of new environments, over the long term as well as the short term.

-– Sternberg (1998)

This definition is somewhat human-centered and can easily be generalized to all life, all agentic interests, all habitats, and all time-scales. And since tacit knowledge refers to skills, Sternberg’s definition can be generalized to “the balancing skills to contribute to the biosphere.” This is what we refer to as generalized wisdom.

Where the application of power generally (but not necessarily) produces benefits to an in-group at the detriment of out-groups, proper co-creation leads to broadly constructive benefits and is a more than zero-sum game. As we argued, this drove and arguably still drives biospheric growth. Note that many agents might still suffer; co-creation manifests broad net benefits, not the absence of harm or suffering. Typically co-creating agents form a community, a group of individuals that each freely and self-guidedly contribute whatever benefits their adequacy can bring.

Co-creating agents need to act on what comes naturally to agents and habitats. They must learn how to promote more natural behavior and prevent behavior leading to broadly detrimental consequences. The Daoist key term ‘Wu Wei,’ reflects this since it “means something like ‘act naturally,’ ‘effortless action,’ or ‘nonwillful action’” (Littlejohn, 2003). Characteristically, it completely misses the urgency of coping strategies and the effort associated with exercising power. Wu Wei is also a way to be authoritative:

… individuals emerge authoritative and powerful as part and parcel of an interconnected web of forces. Therefore, a crucial back-and-forth tug between the self and the various influences and authorities surrounding it is woven in the very fabric of what it means to be a fully attained and empowered individual.

-–(Brindley, 2010, pp. xxvii–xxviii).

Wu Wei is a quite different conception of authority since it does not pertain to realizing specific intended results, but instead is aimed at pervasive optimization (Andringa et al., 2015) and becoming “a fully attained and empowered individual” as “part and parcel of an interconnected web of forces”; what Maslow (1954) refers to as self-actualization. It is this growth process that drives identity development, as much as it promotes general well-being.

Co-creation expresses and relies on highly skilled behaviors of many responsible autonomous individuals who adapt to and use the possibilities of changing situations. As such it is not easy to maintain and somewhat fragile; the highest co-creative quality is difficult to maintain and generally transitory. This is quite different for coping that relies on more basic strategies like mimicry and rule-following and that can be both stable and stultifying.

The complementary properties and behavioral logic of coping and co-creation lead often to opposing strategies. Both aim to increase habitat predictability. Coping does that via imposing behavioral constraints and habitat control to counteract adequacy limits. Co-creation instead promotes the creation of a never-stable network of behaviors that come naturally and unconstrained and that distribute the responsibility for habitat viability over all contributing agents. Implicitly this assumes that participants are willing and able to alleviate their adequacy limits and grow in their ability to co-create.

Coping and co-creation are both essential. But successful coping is short lasting and effective, it ends the cause for its activation and restores co-creation as behavioral default. Unsuccessful coping is ineffective, and hence prolonged. And since the causes for its activation remain valid, it precludes co-creation. This entails that individuals who predominantly cope or co-create develop quite different worldviews, strategies, values, and identities. Hence, they might not be able to understand one another or to collaborate effectively.

Table 2 shows the two separate ontologies of coping and co-creation. It organizes and relates the concepts within each ontology through matching them to complimentary concepts and/or roles in the other ontology. That we are able to do that on a consistent basis, suggests not only the structural differences between coping and co-creation, but also that we are uncovering some basic tenets of life and cognition.

We consider the selection, matching, and precise formulation of these concepts an ongoing process. Hence, its formulations will develop over time; the formulation in the table is our current best.

In part 2 of this paper we apply and extend the proposed framework to identity development and we apply it on a metatheoretical level to two approaches to general well-being. Ontological security as manifestation of coping and psychological safety as manifestation of co-creation. This leads to the extension of both tables and an improved definition of co-creation and the two ontologies that comprise it.

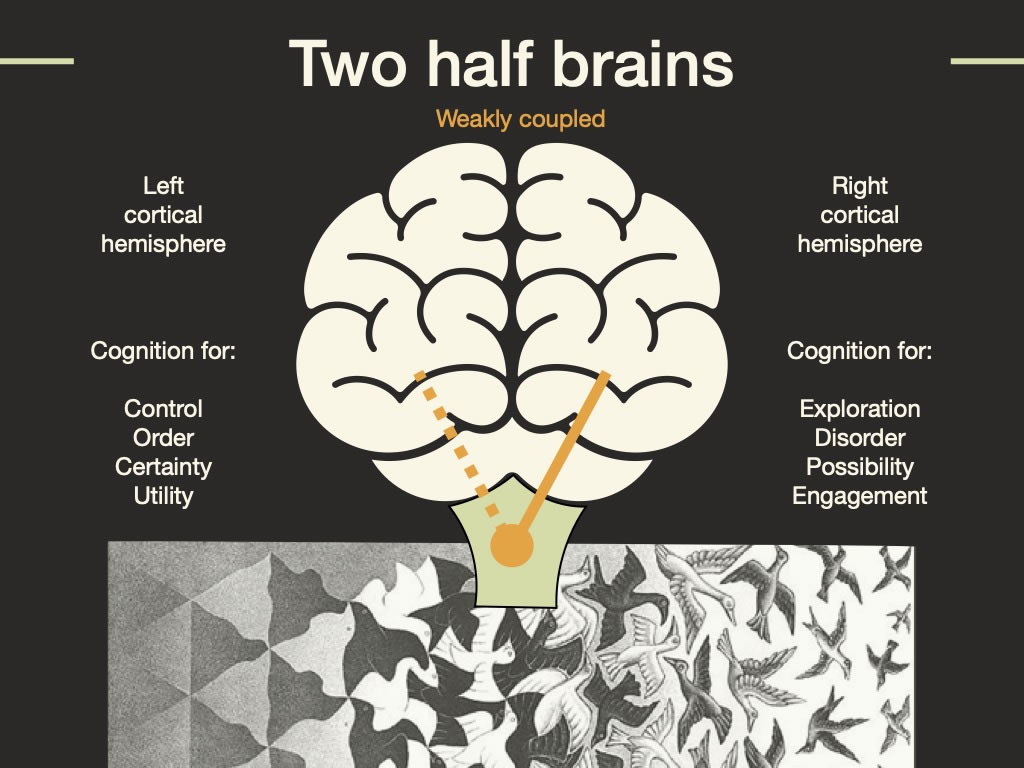

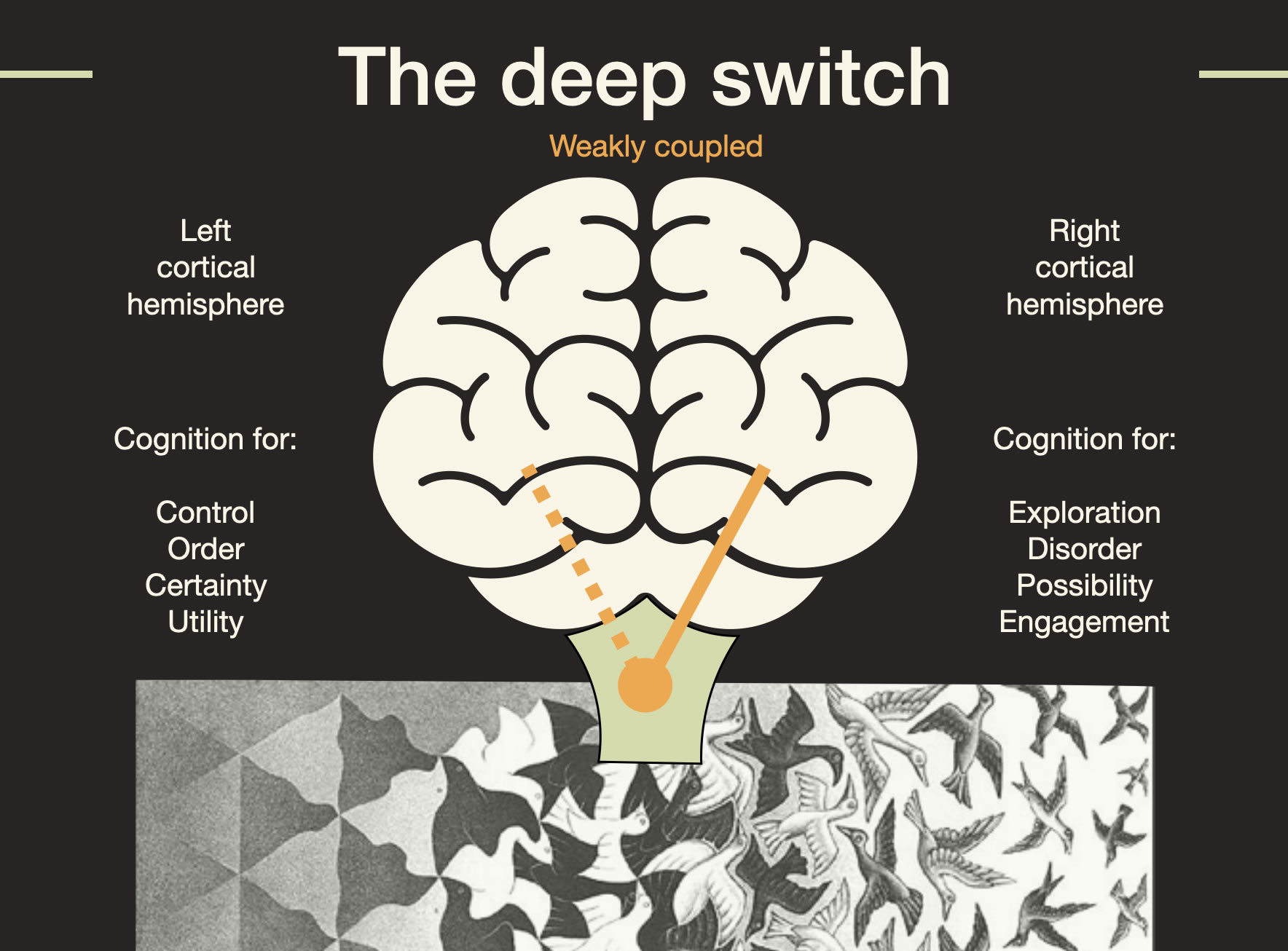

The properties of the coping and the co-creation reflect a close relationship to the properties of the left and the right brain hemispheres as described by McGilchrist in his book “The Master and his Emissary”. Here we derive those properties from the “edge of chaos”. Coping promotes structure, co-creation promotes opportunity.

This is a slightly extended version of Example 1 of the usefulness of the concept of core cognition that we gave of in the application section called “Human Cognition from Life” in our 2015 paper called Cognition from Life (page 11). It develops a connection with Iain McGilchrist’s seminal work on the divide brain.

Two Attitudes Toward the World and Two Brain Hemispheres

In Learning Autonomy (Andringa et al., 2013) we observed that successful life span development is characterized by an ever-improving understanding of reality in combination with an urge (and proven ability) to improve and shape the Umwelt. This fits the description of the co-creation mode that we coupled to the “prevention of problems, consolidation after repletion, and – as much as possible – the creation and maintenance of a safe and sustaining environment with long-term need satisfaction potential.” In Learning Autonomy we interpreted cognitive development (in humans and human-like artificial agents) as learning to master the complexity of the world.

Life is always near the ‘edge of chaos’ (Mora and Bialek, 2011) and if the complexity of the current situation is judged too high we benefit from coping strategies that reduce its complexity and make the situation more tractable and predictable. In Learning Autonomy we referred to the form of cognition that allows us to curtail a complex world as “cognition for order,” “cognition for certainty,” or “control cognition.” We associated this form of cognition with fear and anxiety, detachment, abstract manipulation, and the personality trait ‘closed to experience.’ This description matches with the concepts that we used to describe the coping mode: ‘trying to control the situation,’ ‘reactive problem solving,’ ‘conservation of the essential,’ ‘short-term utility for self-preservation,’ and ‘acceptance of adverse side effects.’

M.C. Escher’s ‘Liberation’ © 2013 The M.C. Escher Company—the Netherlands. All rights reserved. Used by permission. www.mcescher.com).

Yet at other moments we can deal with some additional complexity and allow ourselves to explore the possibilities of the world. Successful, typically playful and purposeless, exploration leads to the discovery of new, generic or invariant structures that make the world a bit more tractable and accessible to agentic influences. This expansion of the understanding of the world fits with the holistic nature of the co-creation mode.

In Learning Autonomy we observed that the two modes we identified matched the description of differences in the way the left and right cerebral hemispheres understand the world and contribute to our existence according to the seminal work “The Master and His Emissary” by McGilchrist (2010). Table 1 of Learning Autonomy provides an comprehensive summary of the reported differences between (and complementarity of) the atti- tudes toward the world associated with the left and the right hemispheres that exemplifies how the coping and the co-creation modes are implemented in modern humanity (and in particular the brains of human individuals).

McGilchrist (2010) argues that our Western societies have become characterized by an ever growing dominance of the left-hemispheric – coping – world-view that favors a narrow focus over the broader picture, specialists over generalists, fragmentation over unification, knowledge and intelligence over experience and wisdom, technical objects over living entities, control over growth and flourishing, and dependence over autonomy. Apparently, despite the huge cultural progress that has been made in the last millennia, humanity shifted more and more toward the coping mode. According to the summary in Figure 1 this is a neither a sign of autopoietic success, nor of viability: on the contrary. Apparently, our understanding of society has not matched society’s complexity growth.

This erosion of the co-creation mode of cognition, and, directly coupled, the resilience reduction of our natural environment, may in fact explain why humanity faces a number of existential problems and in particular has difficulties in realizing a sustainable long-term future: the coping mode, with a focus on pressing problems, intolerance to diversity, and its insensitivity to adverse side-effects as key characteristics, is simply unsuitable to setup the conditions for easy and reliable future need satisfaction.

In McGilchrist’s formulation the right hemisphere is the master and the left hemisphere the servant to be assigned with specific tasks.

We are usually unaware of the switch between coping and co-creation, or alternatively of the switch between the strategies and outlook of our left and right hemisphere.

In the core cognition framework the switch is one between cognition for control, order, certainty, and utility essential when the stakes are high, and cognition for exploration, disorder, possibility, and engagement.

This paper argues for a very visible role of mentally healthy individuals in education. Only these can show children and adolescents what levels of self-development, autonomy, happiness, and growth they can in principle achieve.

Authors: Tjeerd C. Andringa

This paper is about the highest form of mental health attainable: self-actualization. It is not a repetition of what Maslow has said about the topic. Quite on the contrary; it is a more or less independent derivation of the concept of complete mental health and full mental development that validates all Maslow’s insights while providing a scientific foundation.

Maslow was spot on with his description of self-actualization, but he derived this via an intuitive process of little scientific rigor. Most scientific breakthroughs start this way. This paper is an serious, but fairly accessible, underpinning of his intuitions.

I’m not a psychologist. I’m a systems thinker. In particular, I study systems that take responsibility for their own continued existence: living agents. Agents who are very good at that self-actualize. And they prove that through tell-tale characteristics of flourishing. For me self-actualization is not at all a human specific property. In fact, modern humans might not even be very good at it, since many are rather languishing or suffering than flourishing (Keyes, 2005).

In previous papers I have described the demands of survival and flourishing in abstract and general terms that I refer to as core cognition. Core cognition is the cognition that, we postulate, is shared by all of life. With core cognition we derived the requirements of optimal agentic behavior from first principles (Andringa et al., 2015) and with that we can derive the foundations of much of (human) cognition. This gives me a broadly informed and often unique perspective on self-actualization.

In a two-part paper (Andringa & Denham, 2021; Denham & Andringa, 2021, here the combined pdf) we derived the structure of identity from first principles (namely the defining properties of life) and we have also demonstrated that some good intentioned efforts to improve society and its members are doomed to end in a state of pathological normality that is far from self-actualization.

Before that, we (Andringa et al, 2015, pdf) derived 1) the basis for the differences between the brain hemispheres, 2) why the brain has and needs two complementary systems, 3) how power and intelligence serve to prevent an ill-understood world from spinning out of control while understanding and wisdom allow the co-creation of a world in which most problem are prevented. 4) how unicellular cooperation rules explain value differences between US liberals and conservatives, and 5) why positive emotions are the basis for personal and mental growth.