This paper argues for a very visible role of mentally healthy individuals in education. Only these can show children and adolescents what levels of self-development, autonomy, happiness, and growth they can in principle achieve.

Authors: Tjeerd C. Andringa

This paper is about the highest form of mental health attainable: self-actualization. It is not a repetition of what Maslow has said about the topic. Quite on the contrary; it is a more or less independent derivation of the concept of complete mental health and full mental development that validates all Maslow’s insights while providing a scientific foundation.

Maslow was spot on with his description of self-actualization, but he derived this via an intuitive process of little scientific rigor. Most scientific breakthroughs start this way. This paper is an serious, but fairly accessible, underpinning of his intuitions.

I’m not a psychologist. I’m a systems thinker. In particular, I study systems that take responsibility for their own continued existence: living agents. Agents who are very good at that self-actualize. And they prove that through tell-tale characteristics of flourishing. For me self-actualization is not at all a human specific property. In fact, modern humans might not even be very good at it, since many are rather languishing or suffering than flourishing (Keyes, 2005).

In previous papers I have described the demands of survival and flourishing in abstract and general terms that I refer to as core cognition. Core cognition is the cognition that, we postulate, is shared by all of life. With core cognition we derived the requirements of optimal agentic behavior from first principles (Andringa et al., 2015) and with that we can derive the foundations of much of (human) cognition. This gives me a broadly informed and often unique perspective on self-actualization.

In a two-part paper (Andringa & Denham, 2021; Denham & Andringa, 2021, here the combined pdf) we derived the structure of identity from first principles (namely the defining properties of life) and we have also demonstrated that some good intentioned efforts to improve society and its members are doomed to end in a state of pathological normality that is far from self-actualization.

Before that, we (Andringa et al, 2015, pdf) derived 1) the basis for the differences between the brain hemispheres, 2) why the brain has and needs two complementary systems, 3) how power and intelligence serve to prevent an ill-understood world from spinning out of control while understanding and wisdom allow the co-creation of a world in which most problem are prevented. 4) how unicellular cooperation rules explain value differences between US liberals and conservatives, and 5) why positive emotions are the basis for personal and mental growth.

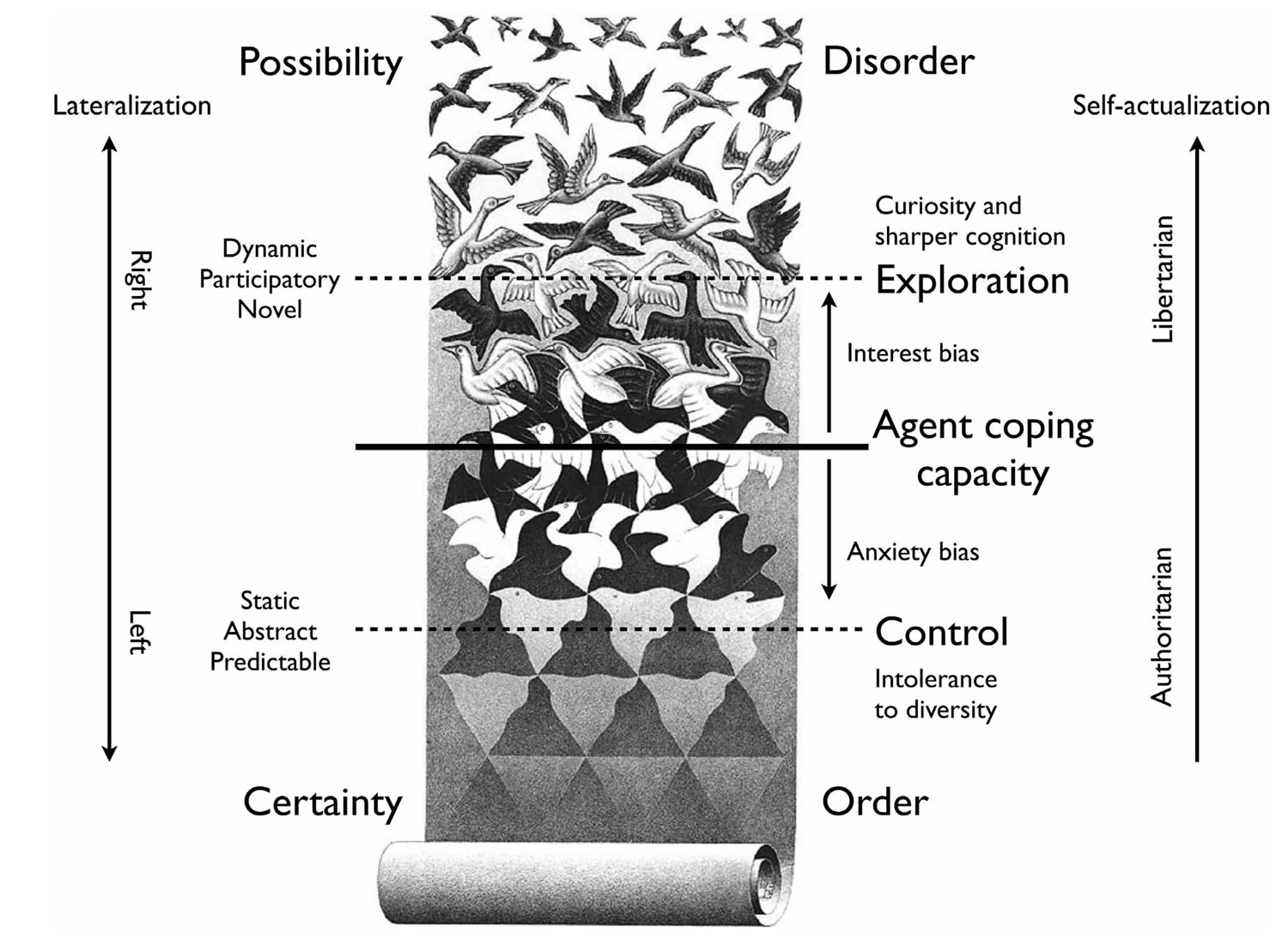

In an older paper on open-ended development called “learning autonomy” (Andringa et al., 2013, pdf) we had laid much of the groundwork by identifying two modes of thought: what we now refer to as coping and co-creation. Using Escher’s tessellation “Liberation”, we showed that coping was actually described by Abraham Maslow as deficiency cognition (D-cognition).

In that paper we described it as cognition for control, certainty, and order since its aim is to realize or restore more manageable conditions to live in (which it may or may not be realistic). We also identified a complementary mode of cognition: cognition for exploration, disorder, possibility, which we now refer to as co-creation. Again Maslow had already described this as being cognition (D-cognition) and he had identified that as the characteristic cognition of self-actualizers.

D-cognition/coping is always associated with a perceived lack of safety and an associated fear of not being able to cope with the situation: it is activated by problems. At the basis, coping aims to realize a less complex world and hence it relies on the various manifestations of social mimicry that all promote oneness and sameness.

Social mimicry can be simple copying of seemingly successful, authoritative or charismatic individuals, but it can also be more indirect via adherence to norms, customs, traditions, rules, checklists, role-models, procedures, ideologies, and laws.

Individuals who express coping do so from a deep and strong (yet mostly unconscious) anxiety to retain or regain control over their lives by imposing a sharable (averaged, static, abstract, predictable) order on the behaviors of self and others. The coping mode’s social motto is: “We are right and you have to adapt your behavior to match ours.” We call this the authoritarian motto.

It is strongly related to Stenner’s (2005) Authoritarian Dynamic: “Intolerance to diversity = authoritarianism x threat level”. Where authoritarianism is a measure of reliance on coping. So the authoritarian dynamic says that the more individuals (and groups) rely on coping and the higher the threat level, the more intolerant to diversity they become.

The complementarity of cognition for control, order, certainty and cognition for exploration, disorder, possibility. From Andringa et al (2013) . (M.C. Escher’s ‘Liberation’ © 2013 The M.C. Escher Company—the Netherlands. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

B-cognition/co-creation complements coping through using the possibilities of the world to add value to the habitat. Where coping aims to solve or otherwise address or suppress problems in standardized or concerted efforts, co-creation success entails the self-directed prevention of problems by reducing barriers to optimal functioning or by finding new ways to realize even better quality of life. We identified the associated continual optimization process as “pervasive optimization": optimizing everything in the context of everything else.

Unlike coping that has specific success states – satisfied or mitigated deficiencies, and more sameness and oneness – co-creation has no definite success states. There are countless ways to realize high quality of life and there is no simple metric to favor one above the other. Where coping relies on social mimicry and the associated reduction of behavioral diversity, co-creation depends on countless self-initiated and unscripted contributions to the world that both increase diversity and quality of life.

We argued that this description of co-creation pertains to all of life and in fact drove the growth of the biosphere in the last 3.8 billion years (Andringa et al, 2015). This is self-actualization on a biosphere level. In fact the biosphere can be interpreted as “Life self-actualizing”.

While Maslow clearly indicated that being-cognition required deficiency-needs to be sufficiently satisfied, he did not say much about the interplay between being-cognition and deficiency cognition. The interplay was in part elucidated by Iain McGilchrist in his book “The master and his emissary” (2010) that describes the two complementary outlooks-to-the-the-world of our two brain hemispheres.

His extremely rich and detailed description of these two outlooks (see table 2 of Andringa et al. 2013) is yet another manifestation of the complementarity of d-cognition/coping and b-cognition/co-creation and he connects this to culture and philosophy.

McGilchrist describes the right hemisphere as the master who tasks the left hemisphere, the emissary, with specific assignments. Problems arise when the emissary, with its characteristic narrow-minded focus, high urgency, and minimal self-reflective abilities takes the master’s role. McGilchrist blames many of society’s problems, backed-up with many historical examples, on the left hemisphere (LH) taking control over matters it is much less competent at than a well-functioning right hemisphere (RH).

We proposed that co-creation (RM) is the natural default mode that is activated in the absence of perceived pressing problems (Andringa et a., 2015; Andringa and Denham, 2021). The coping mode is activated when a situation is deemed problematic (or more generally, benefits from problem solving or focus on detail).

Successful co-creation means prevented pressing problems and flourishing. Its failure leads to unprevented pressing problems. Likewise, successful coping leads to solved problems, while unsuccessful problem solving to perpetuated or new problems. Life success requires therefore both high co-creation skills to prevent problems and high coping skills to address and solve the problems that could not be prevented.

In general low co-creation skills lead to many unprevented problems and low coping skills lead to unsolved or new problems. We refer to an (in part) self-perpetuated situation of continued problems – that keep activating the coping mode – as a coping trap. This is one state of (deeply) suboptimal mental health.

Key dynamics of core cognition. Concepts in white help to realize and protect high viability and are associated with self-avtualization. Concepts in black pertain to coping

The World Health Organization’s' formulated ‘health’ in 1948 as ‘ A state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity ’. Huber (2011) introduced a new concept of health as ‘ The ability to adapt and to self-manage, in the face of social, physical and emotional challenges ’. Huber’s definition focuses on autonomy: if you are able to face social, physical and emotional challenges, then you are healthy, even in the presence of clear symptoms like obesity, anxiety, or an amputation. On the other hand the WHO’s definition demands complete physical, mental, social wellbeing, well above the level of absence of symptoms.

Maslow’s definition of self-actualization as complete mental health is a combination of the key features of both: it is “complete mental and social wellbeing through the ability to adapt and self-manage in the face of social and emotional challenges”. Complete mental health is self-generated and self-maintained and expresses the skills to prevent most problems and effectively solve or otherwise address those that cannot be prevented.

A completely mentally healthy individual expresses being-cognition and co-creation adequacy most of the time and especially to guide long-term or strategic behaviors. Deficiency-cognition and coping is expressed only as short and effective temporary fallback. Self-actualizers therefore successfully maximize the fraction of their life-time co-creating.

This also dovetails with DiPaolo’s (2014) definition of cognitivity. He writes “A system is cognitive when its behavior is governed by the norm of the system’s own continued existence and flourishing”. The more a cognitive system flourishes, the higher its viability, the further it is from death, the less it is restrained by problems, the more it co-creates and expresses being-cognition, and the more it self-actualizes.

Because self-actualization describes complete mental health, it is a health extreme: only a minority (a few percent, depending on the strictness of the definition) of the population manifests and expresses a dominance of co-creation in combination with very effective coping. Formulated like this self-actualization is the skill to prevent most problems and effectively solve or otherwise address those that cannot be prevented.

Skilled actors realize intended and beneficial outcomes, the unskilled do not or even cause harm. Skillful behavior proves proves a high congruence between intention and outcome and hence realistic expectations. Self-actualizers are very skilled in living and hence prove in the vast majority of their actions they generated realistic expectations: they have created a realistic worldview.

Physical reality, for all its intricacies and complications, is completely self-consistent: physical reality is always in states that follow strictly causally from previous states. This makes physical predictable. This predictability is the key prerequisite of skilled behavior and knowledge in general. Living agents base their very existence on the causal nature of reality.

The more pervasively one can predict the outcomes of one’s interactions with the world, the more often these work out as intended. This is what we refer to as a realistic world-view: a resource to generate realistic expectations of interaction with the full breadth of reality. A highly realistic world-view both characterizes and enables self-actualization. And self-actualizers have created that in a uniquely individual process.

In Learning Autonomy (Andringa et al., 2013) we described three phases of which the third depends on the successful mastering of phase 2. In phase 1 the agent learns to master the body. Phase 2 aims to make the mind into a reliable tool. Preconditioned on success in phase 2, phase 3 aims to effectively co-create a highly viable interaction between habitat and self. Phase 2 involves the acquisition the huge body of shared knowledge about the physical, the living, and the cultural world that we derive typically from all forms of social mimicking.

Only if this body of knowledge is sufficiently functional and broadly applicable, one can start to rely on it to engage in truly self-directed endeavors. So only when self-direction provides a net benefit, individuals have access to phase 3: the phase of self-actualization and full human autonomy. We provided a lot of converging evidence for this.

The problem with phase 2 knowledge is that it involves the adoption of shared and consensually adopted knowledge from teachers and peers, a process that Maslow calls enculturation. Knowledge acquired this way is mostly correct and functional and its application is effective in the Pareto sense: you can derive say 80% of the benefit by acquiring this knowledge, but to reach optimal or even correct results you need additional experience to refine the knowledge and to apply it safely in realistic contexts.

This refinement is not only a process that takes considerably longer, it is also a strictly private mental process: one in which you have to learn to trust your mental refinement abilities. And while you learn to trust your own decision and sense making, you develop your own unique and better than average worldview. If you do not, you have to fall back to a mostly consensual shared worldview with lower effectiveness.

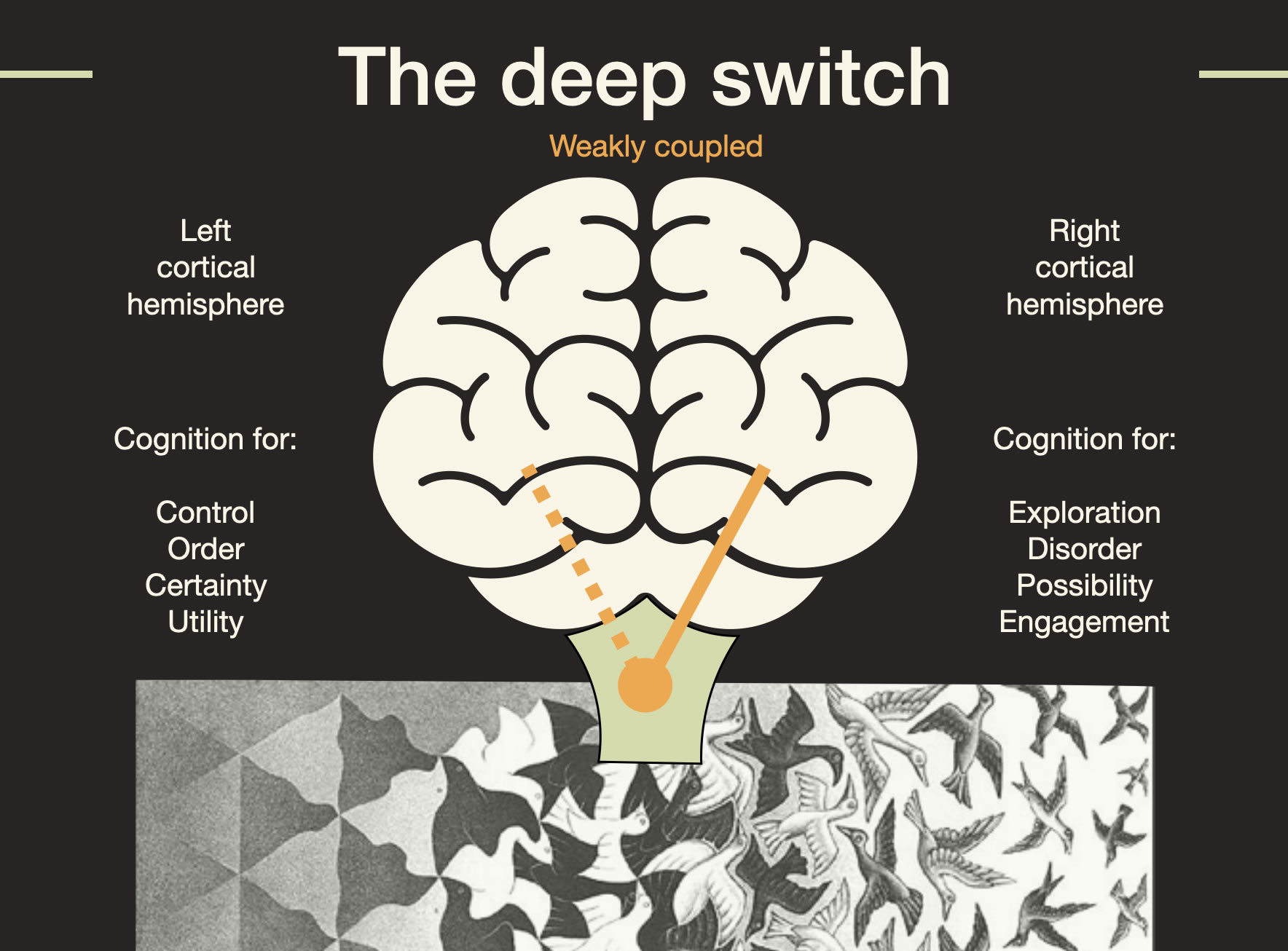

This “switch” from shared, explicit and consensual knowledge to ever more individual, implicit, and self-constructed knowledge determines phase 2 success and gives access to phase 3 and (potential) self-actualization. In McGilchrist’s terminology this corresponds to a shift from left hemispheric dominance to a gradually more prominent role of the right hemisphere and, self-actualization to its dominance.

It also corresponds to a change from memorization via social mimicry, characteristic of coping, to the self-construction of knowledge (on a basis of shared knowledge) and self-direction. It is a switch from cognition for control, order, certainty, and utility to cognition for exploration, disorder, possibility, and engagement. And it is also a switch from reliance on external authority to self-direction (the internalization of the authority role).

The deep switch” caption=“The deep switch signifies the gradually growing reliance on self-constructed knowledge and strategies that at the same time signifies a change from cognition for control, order, certainty, and utility via social mimicry to cognition for exploration, disorder, possibility, and self-guided engagement via the self-construction of knowledge and strategies.

This “deep switch” is a precondition for self-actualization and full mental health. Without making the switch you are limited to the domain of shared consensual knowledge. Depending on the quality of the contributions to the shared knowledge domain its quality can range from totally dysfunctional and toxic to fairly reliable and empowering.

In fact the historian Quigley (1961) claims that the statement “Truth unfolds through a communal process” lies at the foundation of Western culture. Western society has indeed created much valuable knowledge. It also created a lot of knowledge, data, and opinions of questionable utility and unrealistic and unproductive nonsense. These pollute the shared societal narrative and degrade its utility and reliability. Of course, the more dysfunctional the shared narrative, the more difficult it will be to protect against the adoption of disempowering data, ideas, and opinions. I refer to the process of getting rid of this as weeding out toxic enculturation.

Phase 2 depends by and large on copying the behaviors, ideas, strategies, opinions, and talking-points of others: social mimicry. If successful, this is a stepping stone towards the more advanced behaviors in phase 3. For this aspiring self-actualizers need to learn the mental habits to weed ‘toxic enculturation’ because this causes or prolongs problems when relied on and effectively reduces the life-fraction co-creating. And with that it reduces one’s autonomy hence locks one in phase 2.

Self-actualizers prove they succeeded in weeding out the knowledge items and inconsistencies in their worldview with a dominant co-creation mode. Non-self-actualizers suffer from toxic knowledge items and a generally inconsistent world-view that prevent them to consistently reach the higher levels of self-maintained viability and locks them in the coping mode.

This is a process in which (system 2 and system 1) [bullets are draft]

This is a mind that has learned to improve his own thoughts by critical examining them. This is a well-studied and documented process,

Perry (1998), who studied epistemological development in adolescents (in his case Harvard students) has described the associated mindful engagement when he described the features of the educated mind. He wrote:

The educated mind has learned to think about even his own thoughts, it examines the way it orders his data and the assumptions it is making, it compares these with other thoughts that other people might have and adopts whatever this scrutiny of data, ideas, and opinions decides on as most reliable and productive.

In doing so the educated mind learned to think in accordance with reality from which position he can take responsibility for his own stand and negotiate – with respect – with others.

The key point here is that an educated mind self-examines data, ideas, and opinions and replaces these with ever more reliable and productive variants. This habit to make one’s data, ideas, and opinions ever more reliable and productive is not only the process that weeds out toxic enculturation in internal inconsistencies between knowledge items, it is also the driver of self-actualization.

Note that nothing in this definition requires formal education. Formal education might even impede the deep switch when learning focusses solely on the diverse forms of social mimicry (like complying with standardized learning outcomes) and the associated memorization at the cost of the self-construction of knowledge.

Weeding out unproductive and toxic knowledge items is also a characteristic of the achieved identity style. In identity research, the data, ideas, and opinions that one takes for true – one’s worldview – is referred to as self-relevant information. It is self-relevant because what we take as reliable and productive becomes part of our identity or self-theory. Identity can be defined as “a theory of me as actor in the world” or “self-theory” (Berzonsky, 1992): how you define yourself determines how you engage the world. Berzonsky (1992), writes:

The effectiveness of this identity structure or self-theory depends on its pragmatic utility: Does it enable individuals to cope successfully with the stressors and personal problems that are encountered in everyday life? As contextual demands change and new situations are encountered, continued personal effectiveness will depend on the way in which the identity structure or self-theory is revised or conserved.

Self-actualizers know that their set of self-relevant information – their worldview – can and should be improved by identifying and repairing errors, inconsistencies, and missing data and hence they welcome (high quality) information that is “dissonant” (conflicting) with their current world-view because it challenges them to reduce the conflict between their current worldview and potential improvements derived from different perspectives on reality. This find this process also quite pleasurable.

Identity research calls this the informational identity style. This attitude towards information is, as one would expect of something essential to self-actualization, predictive of many aspects of their being. Berzonsky (2011) summarizes the informational identity style as follows:

Individuals with an informational style deliberately search out, process, and evaluate self-relevant information before resolving identity conflicts and forming commitments. They are self-reflective, skeptical about their self-views, interested in learning new things about themselves, and willing to evaluate and modify their identity structure in light of dissonant feedback. Research indicates that an informational style is associated with self-insight, open-mindedness, problem-focused coping strategies, vigilant decision making, cognitive complexity, emotional autonomy, empathy, adaptive self-regulation, high commitment levels, and an achieved identity status. Individuals with high informational scores tend to define themselves in terms of personal attributes such as personal values, goals, and standards.

This description points to an aspect that has not yet been focused on: self-actualizers self-manage personal growth to meet the challenges of changing circumstances (“problem-focused coping”, “modify their identity structure”, and “adaptive self-regulation”). To do so they need to be “self-reflective, skeptical about their self-views, interested in learning new things about themselves, and willing to evaluate and modify their identity structure in light of dissonant feedback”.

Both the description of the educated mind and the informational style rely on a combination of strong co-creation and coping skills with co-creation and the associated enlargement of behavioral repertoire in the lead and coping as an effective fallback.

Self-actualizers are a subpopulation of identity achievement. Individuals with and achieved identity have experienced a period of self-exploration in which they learned to weed out toxic enculturation, where they developed and learned to trust a personal world-view that allows them to (mostly) think and act in accordance with reality.

They have skills and strategies that work reliably and hence do not have to be changed. It seems as if they have committed to particular life courses. But these commitments are not so much a deliberate choice, as a set of reliable and broadly beneficial personal strategies that they continually build on and hence value highly and protect.

The more they self-construct their personal sphere of influence, the more they prevent problems (co-creation) and the more effectively and quickly they address the ones that cannot be avoided, the more they self-actualize. An achieved identity style is indeed a prerequisite to self-actualization.

This then concludes the first part"Self-actualization: what is it?”. Self-actualization is not only near optimal mental health, it is as much a form of optimal living. And this form of optimal living is preconditioned on developing a realistic worldview.

Self-actualization has a number of tell-tale indicators.

In the next part, full mental health will become more meaningful by contrasting it with different forms of existence that fall short of it.

What self-actualizing is will become even clearer by contrasting it to behavioral patterns that are deemed quite normal – and are often the norm – and not normally indicative of sub-optimal mental health. I do this using the structure of identity as has been elucidated in the last 50 years.

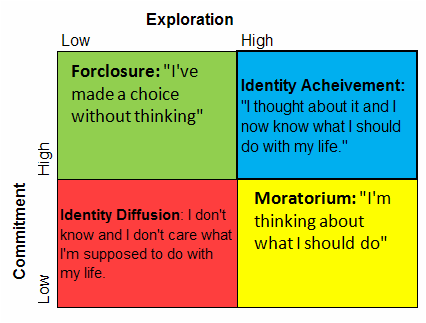

Traditionally, the structure of identity development is depicted in four quadrants. The achieved identity style, including the self-actualizers, is one quadrant. The other quadrants are referred to as the moratorium, the foreclosed, and the diffusive identity style. Self-actualizers engage in characteristic mental and identity development processes. Non-self-actualizer are either:

The four quadrants arise from the interaction of two axes. One axis denotes self-exploration or not. And the second axis firm commitments or not. Self-actualizers are are committed self-explorers.

Depending on the situation (societal, social, physical, physiological) everyone can adopt strategies characteristic of each quadrant. Yet in the context of normal life, we tend to be dominated by behaviors characteristic of one of the quadrants: our identity style (Berzonsky, 1992). In addition, there is a natural life-course development towards self-exploration and commitments. This development can however stall indefinitely if for example the deep switch is avoided or never completed.

In part 2 of our recent paper (Denham & Andringa, 2021) we outlined the deep relation between coping and co-creation adequacy and the structure of identity (Denham & Andringa, 2021). We summarized this in a somewhat complicated figure centered around four strategies to deal with life’s strategies: preventing, solving, controlling, and avoiding problems. The different identity styles rely on different combinations of these, which to a large extend explains the clear differences between the identity styles.

Individuals with the moratorium identity resemble achievers in many respects. Yet they differ characteristically in the absence of stable commitments. Moratoria clearly engage in self-exploration and weed out some toxic enculturation. So they clearly prefer co-creation over coping. But compared to achievers they have lower coping skills, which entails that many problems and situations are not efficiently dealt with and hence linger.

Where problems activate achievers to deal with them quickly and effectively, moratoria tend to avoid them. This makes sense given their low coping skills, but it deprives them of opportunities to develop these and assert themselves with constructive solutions. Without effective coping, they have no way to execute their strategies optimally and they cannot to protect these in times of adversity.

This makes it impossible to execute stable strategies (commit) and instead adapt to circumstances, rather that grow to match the new challenges as achievers do. As preferred co-creators they explore a lot and engage actively with the diversity of the world. Yet this barely leads to the stable life-strategies – commitments – characteristic of achievers.

In addition, low coping skills keep a background of problems active and hence the coping mode is more often active than in achievers. This holds especially in times of anxiety, trouble, and uncertainty, where they can easily fall back to one of the other identity styles.

At the same time their low coping skills make them prefer comfort and restoration even more than others because it allows them to avoid or restore from their background problems. At the same time their co-creation skills make them fairly good in preventing problems. The combination of broad co-creation skills and a lack of high effectiveness inspires them to co-create a world in which they are less likely to be confronted with their own coping inadequacies.

Moratoria are in the process of making the deep switch. They switch between co-creation and coping most clearly of all identity styles. They prefer co-creation and self-exploration, but as weak copers they are unable to quickly end the problems they are faced with. This entails that they have not yet developed the reliance on self-constructed knowledge and strategies. In easy times they do, in difficult times they fall back to coping and social mimicry; in which case they behave like foreclosures or diffusions. In this case they become intolerant to diversity and prevent the personal growth that might allow them to cope better with circumstances. This is the authoritarian dynamic (Stenner, 2005) at work.

Nevertheless, they tend to understand the basics of self-actualization and find it highly desirable. At the same time they find the path towards it quite elusive.

[This part is repetitive]

The identity style that conflicts most with self-actualization is the foreclosed identity. And that is not because they are furthest away from self-actualization (which is the diffusive identity), but because of an exclusive reliance on coping, which actively forecloses self-actualization by suppressing all ‘dissonant information’ through a near exclusive reliance on social mimicry: rule following, procedures, traditions, checklists, ideologies, authority supported narratives, and consensually derived shared knowledge,

On a group level foreclosures are effective copers, but as individuals and groups they are ineffective co-creators. Ineffective co-creation (problem prevention) in combination with unaddressed toxic enculturation entails that foreclosed individuals and their in-group live in a world of structurally unprevented problems. Their high coordinated – hence group-level – coping skills keep these problems usually at manageable levels, but this requires a constant effort to suppress undesired (read potentially unmanageable) diversity.

Because they live in a world of structurally unprevented problems, foreclosed individuals rely on coping because they continually feel a deep and strong (yet mostly unconscious) anxiety that motivated them to retain or regain control over their lives by imposing a sharable (averaged, static, abstract, predictable) order on the behaviors of self and others. Hence they apply the coping mode’s social motto: “We are right and you have to adapt your behavior to match ours.”

This fits with the key strategies of foreclosures to deal with life’s challenges: a combination of solving and suppressing problems. Promoting oneness and sameness can solve some problems, but intolerance to diversity ensures that solutions and improvements are not even considered and hence foreclosures maintain conditions far below optimal. Coping is for survival, not for flourishing.

Stenner (2005) calls potentially undesired diversity a ‘normative threat’: a threat to the normative order and the cohesion and proper functioning of the in-group. Foreclosed individuals insist on “oneness and sameness” in all strategies, opinions, data, habits, traditions, narratives, and beliefs on which the proper functioning of their in-group relies on. This insistence is not a polite wish, but an existential need since they simply no longer have the cognitive apparatus to deal with more effective and productive strategies that conflict with the in-group narrative.

And because of this, they tend to restore – individually, but typically in groups – in-group oneness and sameness first lovingly and if necessary ruthlessly. Any in-group, small or big, whether a cult, ideology, religion, political or sexual orientation, knowledge discipline, nation, cultural or informational subculture, profession, or knowledge bubble, that functions according the logic of coping, promotes sameness and oneness by first identifying and later suppressing dissonant out-group influences. Even the main culture of a region can behave like this.

For foreclosures, commitments are the direct result of excluding out-group options and hence they have no choice other than to act in accordance with the worldview of their in-group. For foreclosures commitments are just expressions of the full and unchanged adoption of the in-group narrative and not of any true self-direction.

So they can commit to a certain in-group carrier path, in which one could them ambitious. And they try to be the best in-group member they can be. But this almost inevitably entails sacrificing individual needs. Burn-outs seem to be a typical manifestation of this when the brainstem, tasked with keeping the body functional, no longer accepts this neglect and shuts down all motivation to continue the neglect.

Individuals with a foreclosed identity have never engaged in serious and successful self-exploration, because they unquestionably adopted the norms, practices, and narratives of the in-group that they are committed members of. They are fully enculturated in-group members who prevent themselves from weeding out the toxic cultural influences of their in-group. Because because if they so that would make them flawed in-group members.

Hence they not only self-censor urges and ideas that conflict with the shared narrative, they also insist that others do so. This entails that with respect to the core narrative of the in-group they tend to be fairly interchangeable, predictable, and de-individualized. This is social mimicry successfully leading to more sameness and oneness. Whatever diversity exists does not conflict with the shared in-group narrative.

The term foreclosed {to rule out or prevent] is actually well chosen. They have not only prevented self-exploration through the mindless adoption of some in-group narrative, but they actively rule out and suppress many perfectly feasible improvements to self, group functioning, and the world if these do not fit in their ideology, narrative, or creed. They implement the authoritarians motto: “We are right and you have to adapt your behavior to match ours”. And Stenner’s (2005) Authoritarian Dynamic in the sense that their intolerance to diversity scales with the normative threat-level they perceive.

Associated with the foreclosed identity comes a specific attitude to information that is referred to as the normative identity style. Berzonsky (2011) describes this normative orientation as follows.

Individuals with a normative orientation internalize and adhere to goals, values, and prescriptions appropriated from significant others and referent groups [in-groups] in a relatively automatic or mindless manner, that is, they make premature commitments without critical evaluation and deliberation. They have a low tolerance for ambiguity and a high need to maintain structure and cognitive closure. Individuals who adopt this protectionist approach function as dogmatic self-theorists whose primary goal is to conserve and maintain self-views and to guard against information that may threaten their “hard core” values and beliefs. This relatively automatic approach to self-construction is associated with a foreclosed identity status and should lead to a rigidly organized self-theory composed of change-resistant self-constructs. A normative orientation is associated with firm goals, commitments, and a definite sense of purpose, but a low tolerance for uncertainty and a strong desire for structure.

Which all fits perfectly with the cognition for certainly, order, and control that we defined earlier. The a priori exclusion of dissonant out-group ideas in combination with a existential dependence on oneness and sameness entails that the shared narrative that unifies the in-group has few options to weed out unproductive, unreliable, or even toxic aspects.

In practice this entails that although the foreclosed individuals express full faith in the veracity of the shared narrative, ideology, or creed, there is no reason to assume that the veracity is any better or less dysfunctional that other in-group narratives. The focus on in-group sameness and oneness prevents that.

Bonhoeffer‘s Theory of Stupidity

[At some point a table with a ]

The fourth and last identity is referred to a as identity diffusion. This is the group of individuals with neither effective coping nor co-creation skills. Like foreclosures they avoided self-exploration (they very well know they might not like what they will find when they do). And like moratoria they avoid problems and hence miss opportunities to learn problem solution skills. As a consequence, diffusions live in a world of unprevented and unsolved problems that they perpetuate habitually. And without these skills and a clear self-theory they respond more than they plan and they have to explain their actions using an ad hoc theory that changes with the circumstances. They therefore show no commitments.

[Self-reflection, they do not like when they reflect, avoid it hence learn little from from their tribulations: search for guidance, guru’s, spiritual leaders, idols, role-models, to mimic. ]

Unlike foreclosed individuals who are effective in-group members, they try to fit in via all types of social mimicry, but often fail to do so with sufficient benefits to self. For example they might crave likes on social media, but dread the prospect of not receiving them. Since they do barely understand the world they live in, they cannot predict the consequences of their own actions and are often confronted with unexpected and unexplainable side-effects (that nevertheless receive some ad hoc explanation). Deep inside they know that they play a big part in perpetuation of their own problems and hence they have great difficulty in engaging in all that is not habitual. This manifests as procrastination, which eventually entails that circumstances rather than their own initiative decide on their life-course.

Yet despite this all,

Because the live in a world of unprevented and unsolved problems (a coping trap) they rey

A diffuse-avoidant orientation involves a reluctance to confront and deal with identity conflicts and issues. If one procrastinates too long, actions and choices will be determined by situational demands and consequences. Such context-sensitive adjustments, however, are more likely to involve transient acts of behavioral or verbal compliance rather than stable, long-term structural revisions in the self-theory. This processing orientation, originally identified as a diffuse orientation is postulated to be typical of individuals categorized as having a diffused identity status. When it became apparent that at least some strategic avoidance was involved, it was referred to as the diffuse/avoidant (confused and/or strategic) orientation. The term diffuse-avoidant (with a dash instead of a slash) currently is preferred because it denotes that the orientation involves more than a confused or fragmented self; it reflects strategic attempts to evade, or at least obscure, potentially negative self diagnostic information. Individuals with a diffuse-avoidant orientation adopt an ad hoc, situation-specific approach to self-theorizing, which should lead to a fragmented set of self-constructs with limited overall unity. They assume a present-oriented, self-serving perspective that highlights immediate rewards and social concerns, such as popularity and impressions tailored for others, when making choices and interpreting events. Diffuse-avoidance is positively associated with efforts to excuse or rationalize negative performances, self-handicapping behaviors, impression management, limited commitment, and an external locus of control.

“I’m dysfunctional and I am convinced that if the whole world changes to accommodate my dysfunctionality that I do not suffer from my dysfunction”

Andringa, T. C., & Angyal, N. (2019). The nature of wisdom: people’s connection to nature reflects a deep understanding of life. Psychology. Journal of the Higher School of Economics, 16(1), 108–126. https://doi.org/10.17323/1813-8918-2019-1-108-126

Andringa, T. C., Bosch, K. A. M. van den, & Vlaskamp, C. (2013). Learning autonomy in two or three steps: linking open-ended development, authority, and agency to motivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00766

Andringa, T. C., Bosch, K. A. M. van den, & Wijermans, N. (2015). Cognition from life: the two modes of cognition that underlie moral behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(362), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00362

Andringa, T. C., & Denham, F. C. (2021a). Coping and Co-creation: One Attempt and One Route to Well-Being. Part 1. Conceptual Framework. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 14(2), 152–170. https://doi.org/10.11621/pir.2021.0210

Berzonsky, M. D. (1992). Identity Style and Coping Strategies. Journal of Personality, 60(4), 771–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00273.x

Berzonsky, M. D. (2011). Handbook of Identity Theory and Research. 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_3

Denham, F. C., & Andringa, T. C. (2021). Coping and Co-creation: One Attempt and One Route to Well-being. Part 2. Application to Identity and Social Well-being. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 14(3), 217–243. https://doi.org/10.11621/pir.2021.0314

Paolo, E. A. D., & Thompson, Evan. (2014). The Enactive Approach (L. Shapiro, Ed.; London; pp. 1–14). The Routledge Handbook of Embodied Cognition.

McGilchrist, I. (2010). The master and his emissary : the divided brain and the making of the Western world (New Haven, Conn.). Yale University Press. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=related:jEFLCk-_psUJ:scholar.google.com/&hl=en&num=30&as_sdt=0,5

Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). Mental Illness and/or Mental Health? Investigating Axioms of the Complete State Model of Health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.73.3.539

Perry, W. G. (1998). Forms of Ethical and Intellectual Development in the College Years. Jossey-Bass.

Stenner, K. (2005). The authoritarian dynamic (New York; First Edition). Cambridge University Press.